- Home

- About

-

Travel

-

Features

- Dyrrachion1081

- Normans in the Balkans

- Manolada 1316

- Kosovo 1389

- Castles on the Danube

- Late Medieval Bosnian Army

- Doboj 1415

- Wallachian and Moldovan troops of the Napoleonic wars

- Anchialos 917

- Slovenian Borderlands

- The Zadruga and the Military Border

- Cretan War in the Adriatic

- Salonika 1916

- Uskoks of Senj

- Siege of Klis 1537

- Eugene in the Balkans

- Moldavian Surprise 1711

- Austro-Turkish War 1737-9

- Militargrenze

- Invading Ottoman Turkey

- Siege of Ragusa 1814

- Russo-Turkish War 1806-12

- Serbian Uprising 1815

- Ali Pasha

- Ottoman Army 1826

- Aleksinac 1876

- Shipka Pass

- Slivnitsa 1885

- Romanian Army 1878

- Austrian forts 19thC

- Kumanovo 1912

- Catalca Lines

- Adrianople 1912-13

- Kajmakcalan 1916

- The other 1918 campaign

- Macedonia air war WW1

- War of the Stray Dog

- Royal Yugoslavian armed forces

- Blunder in the Mountains

- Romanian SS

- Gebirgsjager in the Balkans

- Knights Move 1944

- Vis during WW2

- HLI in the Adriatic

- Adriatic Cruel Seas

- Dalmatian Bridgehead

- Cyprus 1974

- Transnistrian War

- Ottoman Navy Napoleonic wars

- Medieval Balkans

- Balkan lockdown quiz >

- Reviews

-

Armies

- Ancient Greeks

- Pyrrhic army of Epirus

- Dacian wars

- Goths

- Late Roman

- Comnenan Byzantine Army

- Normans

- Serbian medieval

- Albanian medieval

- Wallachian medieval

- Bosnian Medieval

- Catalan Company

- Polish 17C

- Austrian Imperialist

- Ottoman

- Austrian 18thC

- Russian Early 18thC

- Ottoman Napoleonic

- Greek Revolution

- 1848 Hungarian Revolution

- Russian Crimean war

- Romanian Army of 1877

- Ottoman 1877

- Russian 1877

- Balkan Wars 1912-13

- Macedonia WW1

- Greece WW2

- Italian Army WW2

- Gebirgsjager WW2

- Hungary WW2

- Turkey WW2

- Soviet Union WW2

- Bulgaria WW2

- Turkish Korean War Brigade

- Balkan Wars 1990s

- Links

- Books

The Siege of Adrianople 1912-13

|

The First Balkan War began on 8 October, with Montenegro attacking Ottoman positions in Albania. Next, Serbia launched an offensive south towards Skopje in modern North Macedonia, and the Greeks attacked Thessaly and then into Macedonia towards Thessalonica. Finally, with three armies, Bulgaria attacked Turkish Thrace on 18 October. The Bulgarian Second Army surrounded the 50,000 Ottoman garrison in the fortress city of Adrianople (Edirne), while the Bulgarian First and Third Armies swept into Eastern Thrace.

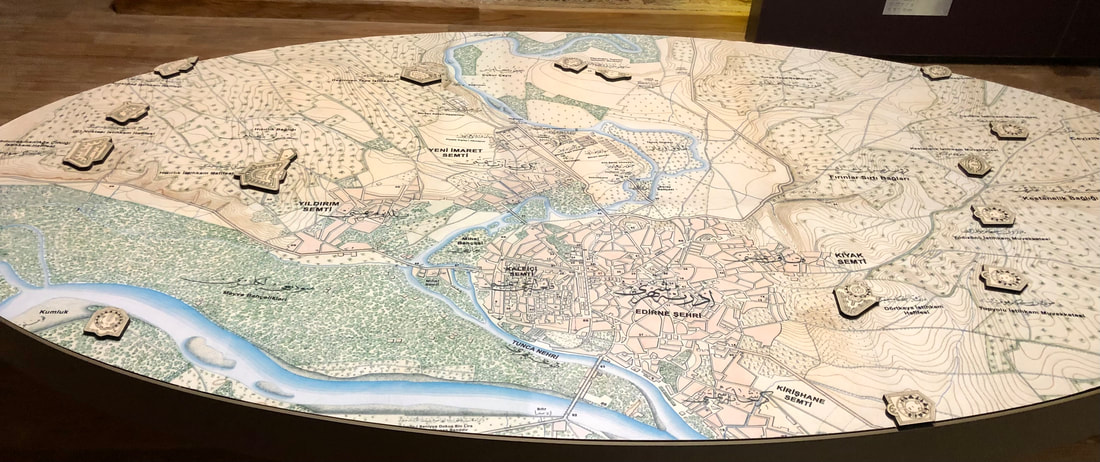

These armies caught and defeated the partially mobilised Ottoman Eastern Army in an open battle around Kirkkilise. The retreating Turkish Army was reorganised and reinforced at the next defensive position at Lüleburgaz-Pinarhisar. The Bulgarian forces were reduced by a detachment to screen the Adrianople fortress and were slightly outnumbered by the Ottoman forces. After fierce fighting and some 20,000 casualties on both sides, the Bulgarian 6th Division captured Lüleburgaz, and the Ottomans withdrew to the Çatalca Lines leaving Adrianople encircled by Bulgarian forces. Adrianople was prepared for this contingency, and the defences covered all approaches to the city. Not only was Adrianople a strategically important hub, but it was also the first Ottoman capital in Europe before the fall of Constantinople. It had a long history of being besieged since Emperor Hadrian built the first fortress in 117AD. John Keegan describes it as 'the most frequently contested spot on the globe.' With German assistance, the city's defences were modernised based on a series of forts three to four kilometres outside the city. These were self-contained with an infantry detachment, machine guns, and artillery linked by telephone. The newly renovated Hidirlik Bastion housing the Museum of the Balkan Wars is the best example of these fortresses and was the HQ of the Turkish commander Ferik Mehmet Sükrü Pasha. These improvements were completed in 1910. However, General von der Goltz recommended moving the strong points to hold key points up to eight kilometres out. The Italian War delayed these improvements, but work started in April 1912 on 18 redoubts on small hills and ridgelines linked by trenches. The plan envisaged a four-year programme, and only a few were completed when the First Balkan War started. Therefore, priority was given to completing the 54-kilometre trench system that linked the redoubts. The peacetime garrison consisted of the IV Corps HQ, 10th Infantry Division, 4th Rifle Regiment, two cavalry brigades to screen the border, and a powerful Fortress Artillery Brigade with 247 guns. These ranged from 75mm to 150mm guns, and even two 75mm anti-aircraft guns. As the war started, the garrison mobilised 1,111 officers and 60,139 men in 19 regular and 30 Redif battalions. However, only about 25 per cent were considered trained. The fortress was well stocked with food and ammunition, and many civilians were evacuated. Refugees had already been expelled from Muslim villages, adding to the numbers. The museum quotes Ernest Hemingway on the condition of refugees from the war as being in 1912. I'm afraid the otherwise excellent museum has got this wrong. He was writing about the consequences of the Greco-Turkish War in 1922. In 1912 he would have been 13 years old, a little young to be reporting on the Balkan Wars! |

|

The Bulgarian Army had been collecting intelligence on the defences for several years, and they regarded it as the strongest position in Europe. This was an exaggerated assessment that influenced the screening strategy for Second Army while the other two armies defeated the Ottoman field army. The screening forces were in place by 27 October, and this was turned into a complete encirclement when reinforcements started to arrive on 6 November. These became available because of the Serbian victory at Kumanovo. The Serbian Timok Infantry Division arrived on the northwest corner of the fortress, followed by the Tuna Infantry Division on 13 November and the Timok Cavalry Regiment. The Serbian contribution to the siege totalled some 47,000 men and 72 guns.

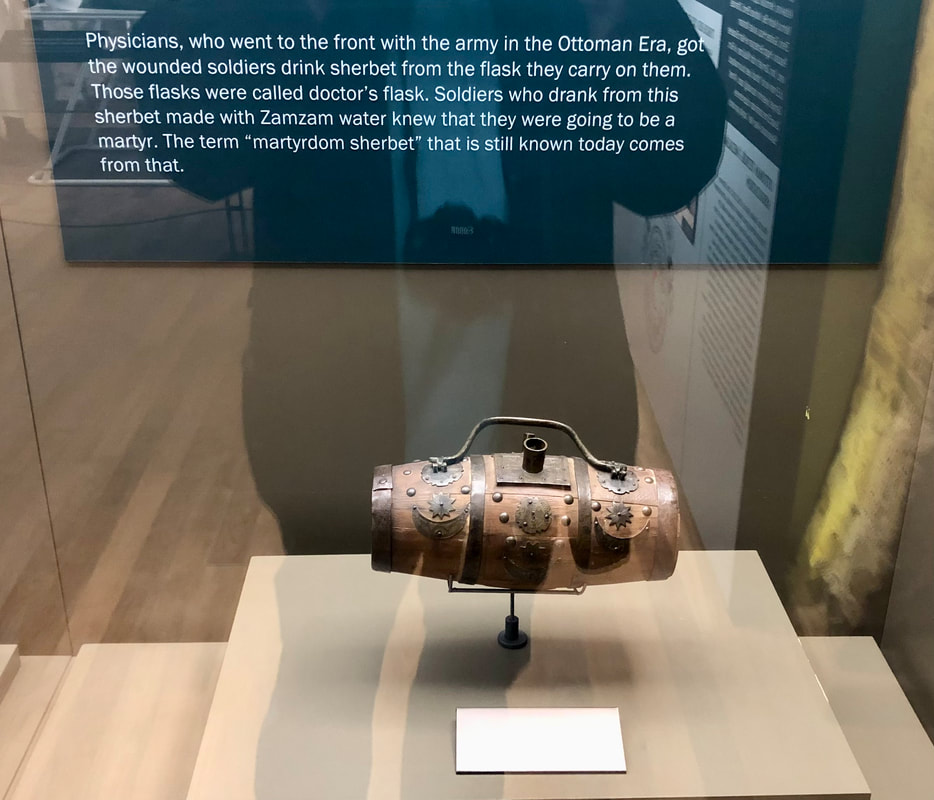

A sustained bombardment of the city began on 10 November but had little impact on the fortress. The Çatalca armistice was extended to Adrianople on 8 December. This respite enabled the Turks to repair a strengthen the fortifications and improve the training of reservists. The Bulgarians did the same and brought up additional heavy artillery. It was a pretty grim winter for the troops on both sides, but the more so for the garrison and civilians who were rationed. Typhoid and Cholera broke out on 18 December, for which there were few remedies. The Turkish military doctor Mehmet Dervis said, ‘We had no medication other than Laudanum, Zeytikafuri, and no food other than tea and rice soup.' Sükrü Pasha requested a relief force but instead got promoted to Lieutenant-General! |

|

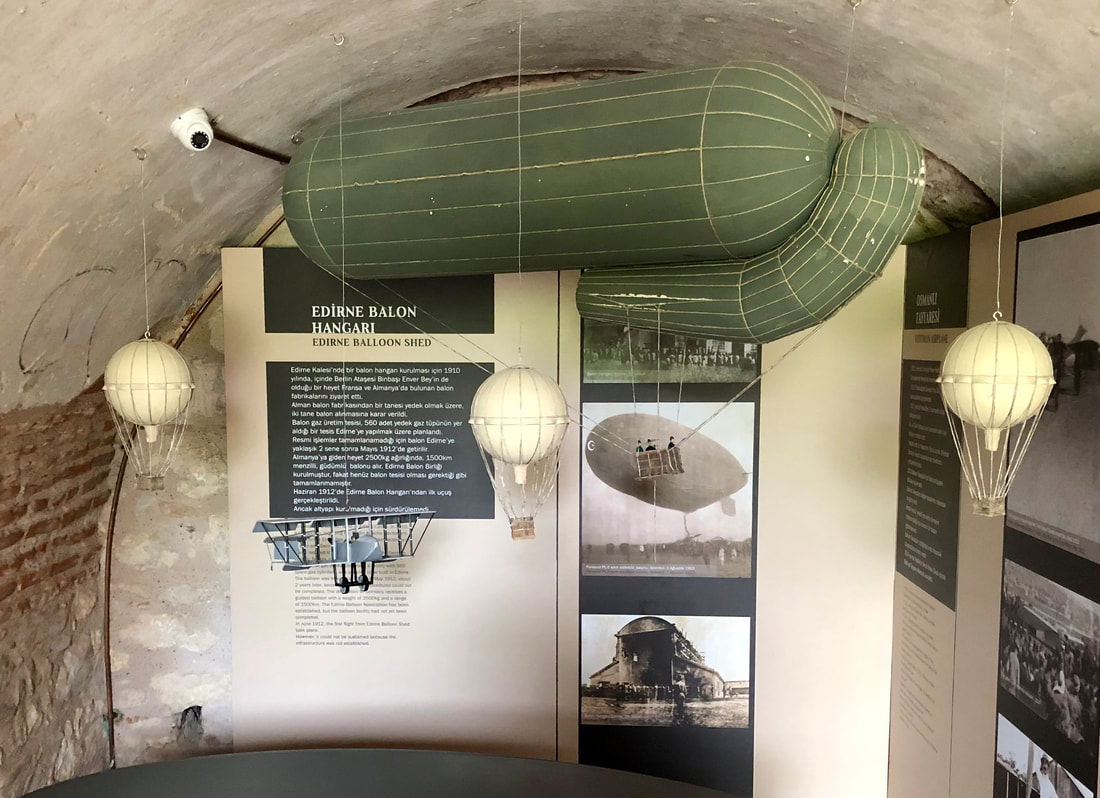

The armistice broke down on 3 February 1913, and Bulgarian and Serbian artillery hit the city in an effort to undermine civilian morale, supported by Bulgarian aircraft dropping propaganda leaflets. The city's population included Bulgarians, Greeks, Armenians and Jews as well Turks. To raise morale, the Ottoman forces organised a sortie on 9 February, which breached the Bulgarian lines, only to be forced back by a determined counter-attack. This was followed by spoiling attacks on other parts of the Bulgarian lines, which were also unsuccessful. Further Serbian heavy artillery arrived on 13 February, but while it destroyed more of the city, it did minor damage to the fortifications. A Bulgarian plane was shot down on 2 February and was discovered to have a Russian pilot. Ottoman countermeasures included balloons, although these flights could not be sustained, and anti-aircraft fire.

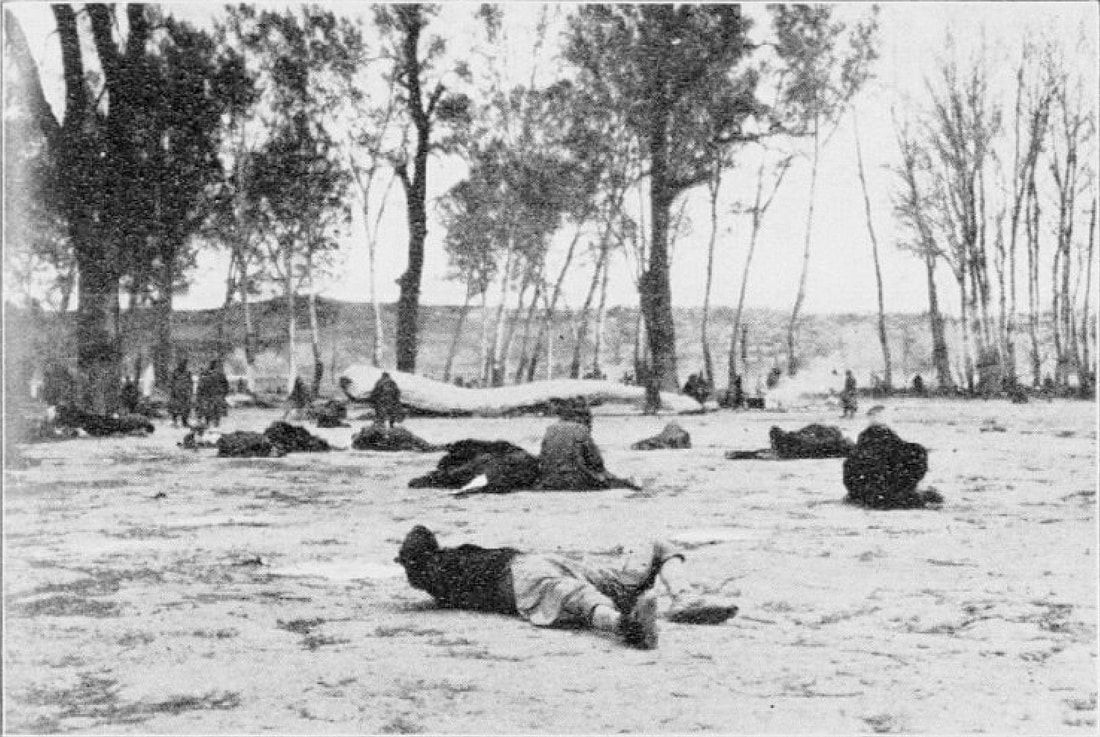

By 12 March, rations had been reduced again, and Sükrü Pasha signalled (the garrison had early radio sets) that offensive actions were no longer possible. Conditions were pretty grim in the Bulgarian and Serbian trenches, and logistics were weak. General Savov decided to storm the fortress on 23 March. The main attack was delivered in the east by the 3rd and 4th Bulgarian Infantry Divisions, supported by a diversionary attack in the south. The diversion drew Ottoman reserves away from the main attack, as did a similar attack in the west by the Serbian Timok Division. The main attack forced the mostly reserve Ottoman troops out of the forward defences, forcing them back to the main fortification line. A night attack on the Baglaronu strong point created a serious breach in the Ottoman defences, which was exploited with further attacks on both sides of this position. Some of the Ottoman positions surrendered without resistance. The Ottoman position was now hopeless, and Sukru Pasha surrendered his command on 26 March. Around 15,000 Turks were killed, and 60,000 went into captivity, many of whom died of disease. The Bulgarian logistic system was simply unable to cope with large numbers of prisoners. Dr Rifat Osman described the food situation; ‘On the second day of the unbearable captivity that began in Sarayici, a quarter of bread was given to the officers, the soldiers were however hungry…. Soaked for a couple of hours, those inedible breads god knows how many days ago were baked, the crusts were green, musty and maggoty in the inside.’ |

|

The Bulgarian losses were set at 18,260. The 1,591 dead and 9,558 wounded in the final assault were unnecessary losses as the garrison would have been starved into surrender by early April. The fixation on Adrianople effectively cost the Bulgarians a share of Macedonia, a cause of the Second Balkan War. During this, they lost Adrianople, which was recaptured on 21 July 1913 and remained part of Turkey.

Erickson argues that the military lessons of the siege may have been misunderstood. International observers believed it was all down to the artillery. However, the artillery failed to destroy the Ottoman concrete and earth strong points. Instead, the Bulgarian infantry and the night assault made the crucial breakthrough. Wargaming Sieges are a bit of a challenge to replicate on the wargames table. The scale and pace of the action make them an unattractive gaming prospect. However, the sorties and the major assaults can be replicated, particularly those in the outer fortifications, which were mostly earth redoubts. Any WW1 set of wargame rules will work for these battles. My preference in 15mm is for Bloody Big Battles, which is supported by an excellent supplement, Bloody Big Balkan Battles, by Konstantinos Travlos. For smaller actions in 28mm, I use Bolt Action. Further Reading The must-read book on the Ottoman Army in the Balkans 1912-13 is Edward Erickson’s Defeat in Detail(Praeger, 2003). For a general history of the wars, Richard Hall's The Balkan Wars, 1912-1913 (Routledge, 2000). For wargamers looking for uniform details, there is Osprey MAA 466, Armies of the Balkan Wars 1912-13 by Philip Jowett, and The Balkan War 1912-1913 by Alexander Vachov (Sofia, 2005). Most of the pictures come from the newly renovated Hidirlik Bastion housing the Museum of the Balkan Wars. This is situated a little way outside the modern city of Edirne and a visit is highly recommended. |