- Home

- About

-

Travel

-

Features

- Dyrrachion1081

- Normans in the Balkans

- Manolada 1316

- Kosovo 1389

- Castles on the Danube

- Late Medieval Bosnian Army

- Doboj 1415

- Wallachian and Moldovan troops of the Napoleonic wars

- Anchialos 917

- Slovenian Borderlands

- The Zadruga and the Military Border

- Cretan War in the Adriatic

- Salonika 1916

- Uskoks of Senj

- Siege of Klis 1537

- Eugene in the Balkans

- Moldavian Surprise 1711

- Austro-Turkish War 1737-9

- Militargrenze

- Invading Ottoman Turkey

- Siege of Ragusa 1814

- Russo-Turkish War 1806-12

- Serbian Uprising 1815

- Ali Pasha

- Ottoman Army 1826

- Aleksinac 1876

- Shipka Pass

- Slivnitsa 1885

- Romanian Army 1878

- Austrian forts 19thC

- Kumanovo 1912

- Catalca Lines

- Adrianople 1912-13

- Kajmakcalan 1916

- The other 1918 campaign

- Macedonia air war WW1

- War of the Stray Dog

- Royal Yugoslavian armed forces

- Blunder in the Mountains

- Romanian SS

- Gebirgsjager in the Balkans

- Knights Move 1944

- Vis during WW2

- HLI in the Adriatic

- Adriatic Cruel Seas

- Dalmatian Bridgehead

- Cyprus 1974

- Transnistrian War

- Ottoman Navy Napoleonic wars

- Medieval Balkans

- Balkan lockdown quiz >

- Reviews

-

Armies

- Ancient Greeks

- Pyrrhic army of Epirus

- Dacian wars

- Goths

- Late Roman

- Comnenan Byzantine Army

- Normans

- Serbian medieval

- Albanian medieval

- Wallachian medieval

- Bosnian Medieval

- Catalan Company

- Polish 17C

- Austrian Imperialist

- Ottoman

- Austrian 18thC

- Russian Early 18thC

- Ottoman Napoleonic

- Greek Revolution

- 1848 Hungarian Revolution

- Russian Crimean war

- Romanian Army of 1877

- Ottoman 1877

- Russian 1877

- Balkan Wars 1912-13

- Macedonia WW1

- Greece WW2

- Italian Army WW2

- Gebirgsjager WW2

- Hungary WW2

- Turkey WW2

- Soviet Union WW2

- Bulgaria WW2

- Turkish Korean War Brigade

- Balkan Wars 1990s

- Links

- Books

Royal Yugoslav Armed Forces

Introduction

The Royal Yugoslav Army (VKJ) during World War Two is a bit of a niche interest. An army that collapsed in just eleven days in April 1941 is also unlikely to be any wargamers idea of a winning force on the tabletop.

Other than a border skirmish or two in the 1920s, the army didn't fire a shot in anger during the inter-war period. However, there are times in the 1930s when war was entirely possible. It is these potential conflicts that caught my attention in recent reading.

The Royal Yugoslav Army (VKJ) during World War Two is a bit of a niche interest. An army that collapsed in just eleven days in April 1941 is also unlikely to be any wargamers idea of a winning force on the tabletop.

Other than a border skirmish or two in the 1920s, the army didn't fire a shot in anger during the inter-war period. However, there are times in the 1930s when war was entirely possible. It is these potential conflicts that caught my attention in recent reading.

|

The Armed Forces

The VKJ was a large army, comprising some 800,000 to 900,000 soldiers after mobilisation. In 1935, they were organised into 24 infantry, one guard, two alpine and three cavalry divisions. This grew to 1.4 million men in 34 divisions by 1939. However, these numbers hide a multitude of problems. Mechanisation was very limited. The country's infrastructure, particularly bridges, meant that only light trucks were practical. There were a handful of WW1 vintage French FT17 tanks, supplemented by Skoda tankettes. Later, 54 new French Renault R35 tanks and 8 Czech SI-D tank destroyers arrived to create two tank battalions. With limited civilian mechanisation, there would have been skill shortages, even if the resources were available to do more. The limited large scale manoeuvres highlighted command and equipment shortages. In 1936, the British military attaché reported shortfalls in the basic kit, including steel helmets, gas masks, tents and small arms ammunition. General officers had not commanded formations larger than a division in the field. Some modern weapons were purchased, primarily from Czech suppliers. These included mountain guns, howitzers, field, flak and anti-tank guns. The army was also reasonably well supplied with light machine guns and mortars. However, the German occupation of Czechoslovakia after the Munich Agreement curtailed this source of modern weapons. The air force (JKRV) had similar problems. In 1935 it could muster around 600 aircraft, mostly of French design. The main types were the Breguet 19 and Potez 25. More modern aircraft were being purchased and produced locally under licence, including the IK-3 monoplane fighter. By 1941 the JKRV had 11 different types of operational aircraft, including the Me109, Do17, SM-79 and Hurricanes. For example, the Do17K was a German aircraft with French engines, Czech cameras, Belgian guns and Yugoslav instruments. You would not want to be a Quartermaster in this air force! The long Adriatic coastline created particular problems for the navy (KJRM). In addition to the Italian enclaves, like Zara (Zadar), it suffered from a lack of interest in the early years, given Serbian control of the armed forces. By 1936, modern vessels were arriving bringing the strength up to 27 surface combatants and four submarines. This grew to 41 ships in 1941, including a light cruiser, three destroyers and 10 MTBs. There was also a small naval aviation force of around 40 aircraft in 1936, which increased to 120 by April 1941. The biggest problem facing the army was morale. The ‘Serbianisation' of the military meant the General Staff was 90% Serb, with only a handful of Croat or Slovene general officers. Ethnic divisions created political instability during the period, and this also impacted the army. Many Croat and Slovene divisions failed to respond to the mobilisation in 1941, and others surrendered almost immediately the German invasion started. |

|

Strategic Position

The map of Yugoslavia highlights the strategic challenges facing the armed forces. Italy had not been given all the territory it had been promised in the secret Treaty of London and Mussolini coveted more of the Dalmatian coast. The main border was in Istria, opposite Slovenia and Croatia. There were also significant Italian garrisons in the Zara enclave and in Albania. Mussolini financed and supported Croatian separatism in the 1920s and 30s. This included the Velebit Uprising in September 1932, when arms were smuggled to the Ustase separatists through Zara. Bulgaria and Serbia had fought a series of wars in the 19thand early 20thcenturies. The main territorial dispute was over Macedonia, and Bulgaria stoked resistance by supporting the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (IMRO). Hungary was another border concern as the Hungarian revisionists campaigned for the recovery of territory with a large Hungarian population. The Hungarian and Czech states went to war in 1938 over such claims. In Yugoslavia, the revisionists targeted Vojvodina, which had a 28% Hungarian population and another 21% were German - leaving 40% Serbs and Croats. |

Yugoslavian foreign policy was aimed at securing their borders. A treaty in 1921 with Romania and Czechoslovakia countered the Hungarians. In 1934, King Alexander brought Greece, Romania and Turkey together in a Balkan Entente.

The assassination of King Alexander on 9 October 1934, in Marseille, was carried out by an IMRO activist supported by two Ustase exiles. The assassins had been trained and armed in Hungary and frequently telephoned Ustaše leader Ante Pavelić, who was living in Italy.

The French and British were trying to create an anti-German alliance with Italy and Yugoslavia, so played down Italian involvement in the assassination. Mussolini was not interested in such an alliance and hoped Alexander's death would lead to civil war in Yugoslavia. As Alexander's son Peter was still a minor, his brother Paul became Regent.

France was Yugoslavia's main significant power ally, following a secret military pact in 1927. Paul was close to Britain, having been educated there. He was at Oxford University with Anthony Eden. The French had reequipped the army in WW1 and continued to support the armed forces. However, Yugoslavia was low on the French and British priorities and either power’s ability to militarily support Yugoslavia at a time of war was limited.

The assassination of King Alexander on 9 October 1934, in Marseille, was carried out by an IMRO activist supported by two Ustase exiles. The assassins had been trained and armed in Hungary and frequently telephoned Ustaše leader Ante Pavelić, who was living in Italy.

The French and British were trying to create an anti-German alliance with Italy and Yugoslavia, so played down Italian involvement in the assassination. Mussolini was not interested in such an alliance and hoped Alexander's death would lead to civil war in Yugoslavia. As Alexander's son Peter was still a minor, his brother Paul became Regent.

France was Yugoslavia's main significant power ally, following a secret military pact in 1927. Paul was close to Britain, having been educated there. He was at Oxford University with Anthony Eden. The French had reequipped the army in WW1 and continued to support the armed forces. However, Yugoslavia was low on the French and British priorities and either power’s ability to militarily support Yugoslavia at a time of war was limited.

German support

Hitler made every effort to cultivate good relations with Yugoslavia, sending Goering to the funeral and he followed up on several occasions. Paul was stridently anti-communist and admired much of what the Nazis had done in Germany.

The Abyssinia crisis in 1935, put Yugoslavia in a quandary. A campaign in Africa would divert Mussolini from invading Yugoslavia, but a weakened League of Nations might embolden Mussolini to undertake further aggression. In the end, Yugoslavia sided with the British, voting for sanctions. This had a significant impact on the economy, as Italy had bought more a third of Yugoslavian exports.

The Germans offered economic assistance, and it was during this period that Dornier bombers and naval purchases were agreed. Hitler emphasised to Mussolini the importance of a peace agreement with Yugoslavia, to draw them away from Britain. Paul was interested in some form of a non-aggression pact with Italy but didn't trust Mussolini.

Yugoslavia worked hard to settle the Hungary-Czechoslovakia conflict of 1938, fearful that Hungarian aggression could move south into the Vojvodina. The Munich Agreement ended that particular phase, but Hungarian ambitions remained.

In June 1939, Paul made a state visit to Germany, staying at Goering’s Karinhall home. Goering's wife even dressed up in Croatian national costume for dinner. Paul's wife Olga had German relatives, and these were part of the diplomatic offensive. However, Paul still refused to join the Axis.

Hitler was furious and believed that Paul's resistance was due to his sympathies for Britain and France. In August 1939, he proposed to Mussolini that Italy should invade Yugoslavia. Mussolini was delighted at the prospect but was advised that the Italian armed forces were in no condition for such an adventure.

As J.B Hoptner said; “Mussolini had the desire in that August of 1939, but not the sinews of war, and thus the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was spared temporarily”.

Hitler made every effort to cultivate good relations with Yugoslavia, sending Goering to the funeral and he followed up on several occasions. Paul was stridently anti-communist and admired much of what the Nazis had done in Germany.

The Abyssinia crisis in 1935, put Yugoslavia in a quandary. A campaign in Africa would divert Mussolini from invading Yugoslavia, but a weakened League of Nations might embolden Mussolini to undertake further aggression. In the end, Yugoslavia sided with the British, voting for sanctions. This had a significant impact on the economy, as Italy had bought more a third of Yugoslavian exports.

The Germans offered economic assistance, and it was during this period that Dornier bombers and naval purchases were agreed. Hitler emphasised to Mussolini the importance of a peace agreement with Yugoslavia, to draw them away from Britain. Paul was interested in some form of a non-aggression pact with Italy but didn't trust Mussolini.

Yugoslavia worked hard to settle the Hungary-Czechoslovakia conflict of 1938, fearful that Hungarian aggression could move south into the Vojvodina. The Munich Agreement ended that particular phase, but Hungarian ambitions remained.

In June 1939, Paul made a state visit to Germany, staying at Goering’s Karinhall home. Goering's wife even dressed up in Croatian national costume for dinner. Paul's wife Olga had German relatives, and these were part of the diplomatic offensive. However, Paul still refused to join the Axis.

Hitler was furious and believed that Paul's resistance was due to his sympathies for Britain and France. In August 1939, he proposed to Mussolini that Italy should invade Yugoslavia. Mussolini was delighted at the prospect but was advised that the Italian armed forces were in no condition for such an adventure.

As J.B Hoptner said; “Mussolini had the desire in that August of 1939, but not the sinews of war, and thus the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was spared temporarily”.

Italian – Yugoslavia ‘What-if’ War 1939

What if Mussolini had ignored the advice of his generals in August 1939, as he was to do on many occasions. The strategic objective was likely to be limited to taking traditional areas of Italian influence in Dalmatia, something that even Churchill was relaxed about. A more extensive invasion was really only practical with German assistance from the north and perhaps Hungarian and Bulgarian support in the east.

Yugoslavia could not ignore these other potential threats, so would not be able to concentrate their army in Dalmatia and Istria.

The Italian invasion plan was likely to have been similar to the planned attack in early 1940 and the next actual invasion in April 1941.

The main assault would come from Istria, today part of Croatia, but in 1939 it was Italian territory as far as the free port of Fiume (Rijeka). This included the naval base at Pola (Pula). The coastal area had a majority Italian population, and ethnic cleansing had forced thousands of Slavs from their homes in the interior. By 1941 the Italians had amassed the 2ndArmy in Istria with one fast, one motorised and three infantry corps. In 1939, the force available would have been smaller, possibly two corps at the most.

A secondary attack would have come from Albania. In 1939 the Italians were still building up their forces in Albania in preparation for a potential attack on Greece, which didn't start until the following year. With the exception of a covering force on the Greek border (Greek treaty obligations did not require them to support Yugoslavia against Italy), the Italians would have been able to deploy a similar strength to that in 1941. This was the 9thArmy consisting of another two infantry corps and support units.

One of the more interesting actions would have been the breakout from Zara (Zadar). In 1941, the Italians had 9,000 men in the Zara garrison, organised into two regiments with support units including motorised AA, field artillery, a tankette company and a Bersaglieri battalion.

The Italians should have been able to achieve air superiority, and they could rely on naval support.

The Yugoslav 4thand 7thArmies were responsible for the defence of the Italian and German frontiers. In 1941 they had five infantry divisions, two mountain brigades and a coastal defence battalion. Other divisions were held in reserve near Zagreb.

The Coastal Defence Command had an infantry division outside Zara and fortress units along the Adriatic coast. There were also reserve divisions in Bosnia.

What if Mussolini had ignored the advice of his generals in August 1939, as he was to do on many occasions. The strategic objective was likely to be limited to taking traditional areas of Italian influence in Dalmatia, something that even Churchill was relaxed about. A more extensive invasion was really only practical with German assistance from the north and perhaps Hungarian and Bulgarian support in the east.

Yugoslavia could not ignore these other potential threats, so would not be able to concentrate their army in Dalmatia and Istria.

The Italian invasion plan was likely to have been similar to the planned attack in early 1940 and the next actual invasion in April 1941.

The main assault would come from Istria, today part of Croatia, but in 1939 it was Italian territory as far as the free port of Fiume (Rijeka). This included the naval base at Pola (Pula). The coastal area had a majority Italian population, and ethnic cleansing had forced thousands of Slavs from their homes in the interior. By 1941 the Italians had amassed the 2ndArmy in Istria with one fast, one motorised and three infantry corps. In 1939, the force available would have been smaller, possibly two corps at the most.

A secondary attack would have come from Albania. In 1939 the Italians were still building up their forces in Albania in preparation for a potential attack on Greece, which didn't start until the following year. With the exception of a covering force on the Greek border (Greek treaty obligations did not require them to support Yugoslavia against Italy), the Italians would have been able to deploy a similar strength to that in 1941. This was the 9thArmy consisting of another two infantry corps and support units.

One of the more interesting actions would have been the breakout from Zara (Zadar). In 1941, the Italians had 9,000 men in the Zara garrison, organised into two regiments with support units including motorised AA, field artillery, a tankette company and a Bersaglieri battalion.

The Italians should have been able to achieve air superiority, and they could rely on naval support.

The Yugoslav 4thand 7thArmies were responsible for the defence of the Italian and German frontiers. In 1941 they had five infantry divisions, two mountain brigades and a coastal defence battalion. Other divisions were held in reserve near Zagreb.

The Coastal Defence Command had an infantry division outside Zara and fortress units along the Adriatic coast. There were also reserve divisions in Bosnia.

The Salonika Campaign ‘What-if’ 1939/40

After the invasion of Poland and the start of WW2, the British and French discussed the possibility of landing a military force at Salonika. This would be something of a re-run of the WW1 campaign. The French General Weygand led the planning, signing himself as ‘CinC of the East Mediterranean Theatre of Operations’.

Yugoslavian ministers had been involved in drawing up the plans and were prepared to co-operate. French officers covertly liaised with Yugoslav officers over airports. Salonika was vital to Yugoslavian participation on the Allied side as it was their only outlet to the Mediterranean. They correctly believed that Mussolini would join the war as soon as he could make gains with little loss. They were also concerned about the Italian build up in Albania, which could result in them seizing Salonika. With the Germans hovering on the northern border, Yugoslavia would have no option other than join the Axis. Yugoslavia had begun to seek a rapprochement with the Soviet Union, but Stalin was not prepared to go as far as enforcing neutrality in the Balkans.

The British, as in WW1, were less keen than the French. They favoured the idea of a neutral Balkan bloc strong enough to withstand German pressure. This would build on the 1938 Balkan Entente, but Bulgaria wanted territorial revisions in Turkish Thrace and the southern Dobruja in Romania. Discussions on this option ended when the moderate Bulgarian government was overthrown in February 1940.

Turkey would be an important player in this strategy. Their first priority was to regain military control of the Straits, which they achieved at the Montreux Conference in 1936. After that, they played all the leading powers off against each other, while maintaining a neutral stance overall. The Turkish foreign minister hinted to the British at least that they would fight in alliance with whichever belligerent offered the most significant inducement.

Turkey also wanted to extend its border in Thrace at Bulgaria's expense. In 1938 they began to concentrate units along the Bulgarian border. In February 1940 they threatened to cross the Maritza River but backed off when Bulgaria claimed to have German support.

The best the allies could achieve was a Friendship Declaration with Turkey, which had no military significance, and even that was opposed by pro-German Turkish generals. Turkey would fight for its own ground, not that of others.

All of the allies Balkan planning came to nothing when Hitler invaded the Low Countries and France in May 1940. Turkey avoided their rather vague obligations and others in the Balkan Pact did likewise.

Yugoslavia was spared an invasion in 1940 because the Germans told them not to and the state of military unpreparedness. General Graziani told Mussolini that the army might be bottled up as it neared the Sava River. Even Count Ciano concluded that it was a non-starter.

After the invasion of Poland and the start of WW2, the British and French discussed the possibility of landing a military force at Salonika. This would be something of a re-run of the WW1 campaign. The French General Weygand led the planning, signing himself as ‘CinC of the East Mediterranean Theatre of Operations’.

Yugoslavian ministers had been involved in drawing up the plans and were prepared to co-operate. French officers covertly liaised with Yugoslav officers over airports. Salonika was vital to Yugoslavian participation on the Allied side as it was their only outlet to the Mediterranean. They correctly believed that Mussolini would join the war as soon as he could make gains with little loss. They were also concerned about the Italian build up in Albania, which could result in them seizing Salonika. With the Germans hovering on the northern border, Yugoslavia would have no option other than join the Axis. Yugoslavia had begun to seek a rapprochement with the Soviet Union, but Stalin was not prepared to go as far as enforcing neutrality in the Balkans.

The British, as in WW1, were less keen than the French. They favoured the idea of a neutral Balkan bloc strong enough to withstand German pressure. This would build on the 1938 Balkan Entente, but Bulgaria wanted territorial revisions in Turkish Thrace and the southern Dobruja in Romania. Discussions on this option ended when the moderate Bulgarian government was overthrown in February 1940.

Turkey would be an important player in this strategy. Their first priority was to regain military control of the Straits, which they achieved at the Montreux Conference in 1936. After that, they played all the leading powers off against each other, while maintaining a neutral stance overall. The Turkish foreign minister hinted to the British at least that they would fight in alliance with whichever belligerent offered the most significant inducement.

Turkey also wanted to extend its border in Thrace at Bulgaria's expense. In 1938 they began to concentrate units along the Bulgarian border. In February 1940 they threatened to cross the Maritza River but backed off when Bulgaria claimed to have German support.

The best the allies could achieve was a Friendship Declaration with Turkey, which had no military significance, and even that was opposed by pro-German Turkish generals. Turkey would fight for its own ground, not that of others.

All of the allies Balkan planning came to nothing when Hitler invaded the Low Countries and France in May 1940. Turkey avoided their rather vague obligations and others in the Balkan Pact did likewise.

Yugoslavia was spared an invasion in 1940 because the Germans told them not to and the state of military unpreparedness. General Graziani told Mussolini that the army might be bottled up as it neared the Sava River. Even Count Ciano concluded that it was a non-starter.

|

Wargaming

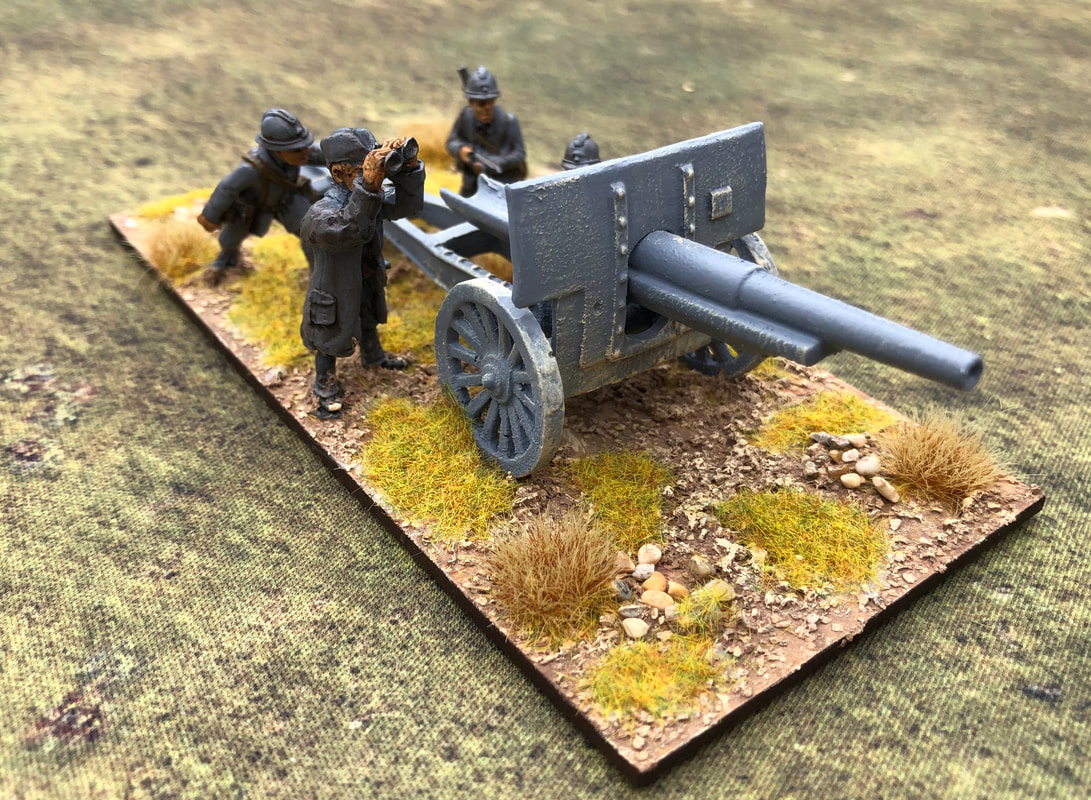

Wargamers have never had it so good in terms of the range of miniatures available. However, there are limits, and an army that lasted only a few weeks in combat is at that limit. Fortunately, all is not lost. The Yugoslav infantry uniform is essentially the same as the French, for which there are plenty of options in all scales. A few Serbian WW1 officers with the distinctive cap, adds a bit of Yugoslavian colour. My own collection is mostly from the Warlord range in 28mm, supplemented by Crusader Miniatures. FT17 and R35 tanks are again available from French ranges. Artillery is more challenging as the obscure Czech pieces are not readily available. AGN Miniatures make the German adaptation of the 47mm ATG, the Pak 38(t), which although the gun shield is a bit large, is pretty close. Mad Bob Miniatures do the 105mm field gun. There is no handy Osprey to consult on uniform details. The best source I have is Andrew Mollo’s Armed Forces of WW2, which has some good colour plates. If you want to see and play with this army, it will be the GDWS participation game at the Falkirk Carronade show in May 2019. |

Further Reading

Andrew Mollo – Armed forces of WW2, Orbis 1981

J.Hoptner - Yugoslavia in Crisis 1934 – 1941, Columbia Press 1963

Neil Balfour & Sally Mackay - Paul of Yugoslavia, Hamilton 1980

Christopher Shores - Air War for Yugoslavia, Greece and Crete, Grub Street 1987

Frank Weber- The Evasive Neutral, Missouri Press 1979

George Blau – Invasion Balkans, Burd Street press 1979

Samo Kristen - The birth of tragedy from the spirit of farce: dubious and real territorial assurances by Great Britain to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the 1936-1941 period- Razprave in gradivo, Dec 2011, Vol.66, pp.64-104

Andrew Mollo – Armed forces of WW2, Orbis 1981

J.Hoptner - Yugoslavia in Crisis 1934 – 1941, Columbia Press 1963

Neil Balfour & Sally Mackay - Paul of Yugoslavia, Hamilton 1980

Christopher Shores - Air War for Yugoslavia, Greece and Crete, Grub Street 1987

Frank Weber- The Evasive Neutral, Missouri Press 1979

George Blau – Invasion Balkans, Burd Street press 1979

Samo Kristen - The birth of tragedy from the spirit of farce: dubious and real territorial assurances by Great Britain to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the 1936-1941 period- Razprave in gradivo, Dec 2011, Vol.66, pp.64-104

Postscript

The territories fought over have recently become a modern day political controversy . At a commemoration of a World War II massacre that took place on the border between Italy and Slovenia, Italian conservative politician Antonio Tajani declared near the city of Trieste: “Long live Trieste, long live Italian Istria, long live Italian Dalmatia, long live Italian exiles.” The region of Istria includes parts of present-day Italy, Slovenia and Croatia. Dalmatia forms part of Croatia. Both areas were occupied by Italian fascists during World War II.