- Home

- About

-

Travel

-

Features

- Dyrrachion1081

- Normans in the Balkans

- Manolada 1316

- Kosovo 1389

- Castles on the Danube

- Late Medieval Bosnian Army

- Doboj 1415

- Wallachian and Moldovan troops of the Napoleonic wars

- Anchialos 917

- Slovenian Borderlands

- The Zadruga and the Military Border

- Cretan War in the Adriatic

- Salonika 1916

- Uskoks of Senj

- Siege of Klis 1537

- Eugene in the Balkans

- Moldavian Surprise 1711

- Austro-Turkish War 1737-9

- Militargrenze

- Invading Ottoman Turkey

- Siege of Ragusa 1814

- Russo-Turkish War 1806-12

- Serbian Uprising 1815

- Ali Pasha

- Ottoman Army 1826

- Aleksinac 1876

- Shipka Pass

- Slivnitsa 1885

- Romanian Army 1878

- Austrian forts 19thC

- Kumanovo 1912

- Catalca Lines

- Adrianople 1912-13

- Kajmakcalan 1916

- The other 1918 campaign

- Macedonia air war WW1

- War of the Stray Dog

- Royal Yugoslavian armed forces

- Blunder in the Mountains

- Romanian SS

- Gebirgsjager in the Balkans

- Knights Move 1944

- Vis during WW2

- HLI in the Adriatic

- Adriatic Cruel Seas

- Dalmatian Bridgehead

- Cyprus 1974

- Transnistrian War

- Ottoman Navy Napoleonic wars

- Medieval Balkans

- Balkan lockdown quiz >

- Reviews

-

Armies

- Ancient Greeks

- Pyrrhic army of Epirus

- Dacian wars

- Goths

- Late Roman

- Comnenan Byzantine Army

- Normans

- Serbian medieval

- Albanian medieval

- Wallachian medieval

- Bosnian Medieval

- Catalan Company

- Polish 17C

- Austrian Imperialist

- Ottoman

- Austrian 18thC

- Russian Early 18thC

- Ottoman Napoleonic

- Greek Revolution

- 1848 Hungarian Revolution

- Russian Crimean war

- Romanian Army of 1877

- Ottoman 1877

- Russian 1877

- Balkan Wars 1912-13

- Macedonia WW1

- Greece WW2

- Italian Army WW2

- Gebirgsjager WW2

- Hungary WW2

- Turkey WW2

- Soviet Union WW2

- Bulgaria WW2

- Turkish Korean War Brigade

- Balkan Wars 1990s

- Links

- Books

Prince Eugene in the Balkans

|

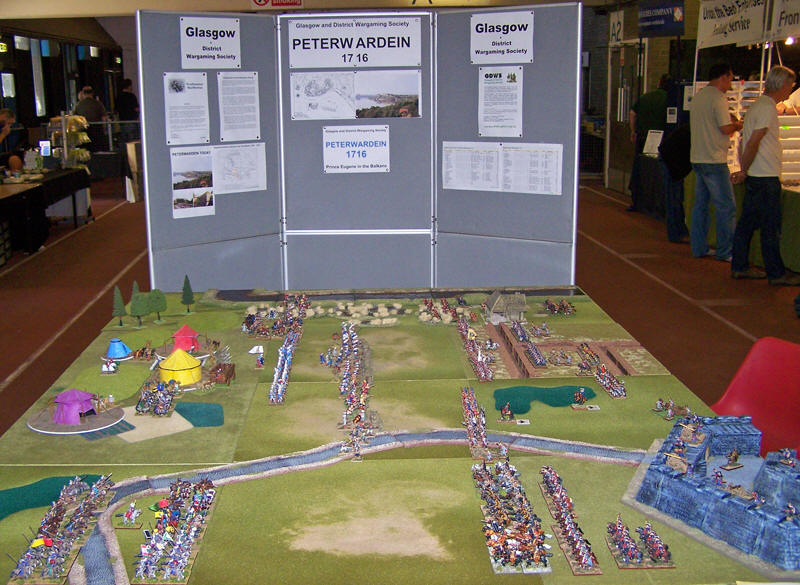

In 2006 Glasgow and District Wargaming Society ran three display games based on the theme of Prince Eugene in the Balkans. This feature sets out the historical background to the three major battles Zenta 1697, Peterwardein 1716 and Belgrade 1717.

Prince Eugene of Savoy is best known to British readers as the erstwhile ally of Marlborough during the wars against Louis XIV. However, it was in Eastern Europe fighting against the Ottoman Empire that he both learnt the art of war and won some of his greatest victories. Eugene was was born in France and brought up in the court circles of Louis XIV. It was only after being refused entry to the French army that he fled France and took service with the Hapsburg Emperor Leopold I. This was 1683 and Leopold needed all the help he could get with the Grand Vizier, Kara Mustapha besieging Vienna. The War of the Holy League Eugene joined the command of his cousin Louis of Baden, which formed part of the Lorraine’s Imperial army. Allied with Sobieski’s Poles they drove the Turks from Vienna. This was Eugene’s first action and he was presented with golden spurs in recognition of his bravery. He was given the Colonelcy of the Dragoon Regiment Kufstein and spearheaded the armies advance into Hungary. For the next three years his regiment was in the thick of the action. At the battle of Szent Endre 1684 the charge of his regiment broke the Turks leading the allies to Buda where Eugene is again mentioned in dispatches in the defeat of the relief army. His success lead to promotion as Major-General in 1685 and he was twice wounded in the eventual capture of Buda in the following year. The Ottoman army responded in 1687 and battle was joined at Berg Harsan (near Mohacs). Ottoman troops repulsed by Imperial firepower were counterattacked by Eugene’s cavalry brigade and driven from the field. Eugene was selected to convey the good news to the Emperor and was promoted to divisional command as Feldmarschall-Lieutenant. He was only 24 years of age. The following year Eugene was at the siege of Belgrade which fell more easily than Buda. Eugene was not present at the fall of the citadel due to a serious wound that forced him to return to Vienna. Eugene did not return to the eastern front as his talents both military and diplomatic were needed in Savoy against the French. |

The Campaign of 1697

The failed campaigns of 1695-96 were led by the Elector of Saxony who after Sobieski’s death was elected to the Polish throne. This enabled the Emperor to pass command of the army in Hungary to Prince Eugene of Savoy in 1697.

He joined his force of 30,000 men at Peterwardein on 27 July with orders to stand on the defensive. The Ottoman Sultan Mustapha personally lead his army north from Belgrade along the River Tisza on 19 August. Eugene also went North linking up with reinforcements from Hungary which strengthened his army to 50,000 men. Mustapha moved on Szeged and Eugene followed with his Hussars limiting Mustapha’s intelligence. The Sultan decided to give up the advance on Szeged and cross the River Theiss (Tisza) at Zenta and then advance into Transylvania.

The Battle of Zenta 1697

On 11 September a captured Pasha disclosed that whilst the Sultan and most of his heavy artillery had crossed the river the Grand Vizier with the entire infantry, part of the cavalry and more than 100 guns were still entrenched in the bridgehead. Eugene rushed his army to the high ground above Zenta.

Eugene’s right wing formed up on the river bank commanded by Heister. The centre commanded by Count Reuss with and on the left Guido Starhemberg completed the encirclement of the bridgehead with a left hook. Eugene’s second in command and cavalry commander was Prince de Commercy. Swarms of Ottoman cavalry attacked the centre but were driven off by the Imperial cavalry supported by infantry and light artillery.

The outer Ottoman defences consisted of uncompleted entrenchments. This was supported by a second line that included an old Imperial storehouse and a wall strengthened by palisades. Eugene’s left wing infantry used a sandbank to get behind the Turkish defences and threaten access to the bridge while his right wing joined up in a wide semicircle. Both sides had reached the river some two hours before sunset. Eugene then ordered a general assault on the entrenchments. Ottoman morale was affected by the flanking attack but the Janissaries in particular fought on before breaking in panic for the river.Some 20,000 Turks including the Grand Vizier and the Aga of the Janissaries were slaughtered and a further 10,000 drowned. Eugene’s army claimed only 300 dead. This victory was decisive and lead to the Treaty of Karlowitz 1699 in which the Hapsburgs gained all of Hungary and Transylvania except the Banat of Temesvar. Eugene’s reputation was made across Europe.

The failed campaigns of 1695-96 were led by the Elector of Saxony who after Sobieski’s death was elected to the Polish throne. This enabled the Emperor to pass command of the army in Hungary to Prince Eugene of Savoy in 1697.

He joined his force of 30,000 men at Peterwardein on 27 July with orders to stand on the defensive. The Ottoman Sultan Mustapha personally lead his army north from Belgrade along the River Tisza on 19 August. Eugene also went North linking up with reinforcements from Hungary which strengthened his army to 50,000 men. Mustapha moved on Szeged and Eugene followed with his Hussars limiting Mustapha’s intelligence. The Sultan decided to give up the advance on Szeged and cross the River Theiss (Tisza) at Zenta and then advance into Transylvania.

The Battle of Zenta 1697

On 11 September a captured Pasha disclosed that whilst the Sultan and most of his heavy artillery had crossed the river the Grand Vizier with the entire infantry, part of the cavalry and more than 100 guns were still entrenched in the bridgehead. Eugene rushed his army to the high ground above Zenta.

Eugene’s right wing formed up on the river bank commanded by Heister. The centre commanded by Count Reuss with and on the left Guido Starhemberg completed the encirclement of the bridgehead with a left hook. Eugene’s second in command and cavalry commander was Prince de Commercy. Swarms of Ottoman cavalry attacked the centre but were driven off by the Imperial cavalry supported by infantry and light artillery.

The outer Ottoman defences consisted of uncompleted entrenchments. This was supported by a second line that included an old Imperial storehouse and a wall strengthened by palisades. Eugene’s left wing infantry used a sandbank to get behind the Turkish defences and threaten access to the bridge while his right wing joined up in a wide semicircle. Both sides had reached the river some two hours before sunset. Eugene then ordered a general assault on the entrenchments. Ottoman morale was affected by the flanking attack but the Janissaries in particular fought on before breaking in panic for the river.Some 20,000 Turks including the Grand Vizier and the Aga of the Janissaries were slaughtered and a further 10,000 drowned. Eugene’s army claimed only 300 dead. This victory was decisive and lead to the Treaty of Karlowitz 1699 in which the Hapsburgs gained all of Hungary and Transylvania except the Banat of Temesvar. Eugene’s reputation was made across Europe.

The Conflict Resumed

At the conclusion of the War of Spanish Succession (WSS) the Austrian Emperor Joseph 1 planned a campaign in the Balkans to follow up on the successes (Zenta 1697) before French expansion in the west dominated Imperial attention.

However, it was the Ottoman’s who made the first move following a successful campaign against Russia in 1711. They declared war against Venice and had recovered the Morea by September 1715. The Austrian’s were still recovering from the WSS and sought to mediate without success. In April 1716 the Emperor signed an alliance with Venice and massed some 51,000 troops in Hungary. The Ottoman’s took the initiative crossing the Sava River near Belgrade they advanced on the fortress town of Peterwardein.

Battle of Peterwardein – 5 August 1716

Eugene arrived at Peterwardein on 9 July with a force of around 60,000 men, including 20,000 cavalry, to face the advancing Ottoman army of over 100,000 commanded by the Grand Vizier, Damad Ali Pasha. Damad had successfully ejected the Venetians from the Morea and had a reputation as a competent commander.

By early August the Ottomans had reached Peterwardein following a cavalry clash with Count Palffy and constructed a hasty defensive position. Rather than allow the Ottomans to wear themselves out on Peterwardein’s modern defences he decided to take the offensive on 5 August. He feared the demoralising effect on his troops of a long period of inactivity and the cavalry skirmish confirmed his view of the technical superiority of his army.

Eugene deployed his army with one flank on the Danube and the other on the fortifications utilising old entrenchments thrown up in 1695. His infantry centre was commanded by Starhemberg supported by a second line under Bevern and a reserve under Loffelholz. On the more open left flank were six infantry battalions commanded by Prince Alexander of Wurtemberg and the cavalry led by Palffy. The smaller right flank consisted of four regiments commanded by Ebergenyi in boggy ground unsuitable for cavalry. A fierce storm damaged the Danube bridges and this delayed the Imperial deployment allowing the Ottomans time to react. The Ottoman cavalry deployed opposite the Austrian cavalry with the janissaries in the centre. The remaining troops skirmished through the morass on the Ottoman left.

Wurtemburg began the battle by advancing the left wing infantry and capturing the Ottoman gun positions. Palffy’s cavalry then charged the Ottoman horse driving them from the field. However, the centre made slower progress held up by small defensive positions. The Janissaries then counter attacked and pushed Starhemberg back to his start line that, even supported by Bevern’s second line, was barely holding. Eugene then ordered Wurtemburg to wheel right and take the exposed Ottoman centre in the flank while he sent the reserve under Loffelholz to secure the centre. The Ottoman cavalry pushed back by Palffy were unable to support this flank. The Janissaries lost hope and even a desperate charge by Damad Ali Pasha, in which he was killed, failed to rally his troops.

The Austrians lost over 3000 men and the Ottomans more than double that including the Grand Vizier. The Ottoman camp with its rich booty and 172 cannon was captured. Eugene pressed on quickly to besiege Temesvar an essential stage towards the ultimate goal of capturing Belgrade.

At the conclusion of the War of Spanish Succession (WSS) the Austrian Emperor Joseph 1 planned a campaign in the Balkans to follow up on the successes (Zenta 1697) before French expansion in the west dominated Imperial attention.

However, it was the Ottoman’s who made the first move following a successful campaign against Russia in 1711. They declared war against Venice and had recovered the Morea by September 1715. The Austrian’s were still recovering from the WSS and sought to mediate without success. In April 1716 the Emperor signed an alliance with Venice and massed some 51,000 troops in Hungary. The Ottoman’s took the initiative crossing the Sava River near Belgrade they advanced on the fortress town of Peterwardein.

Battle of Peterwardein – 5 August 1716

Eugene arrived at Peterwardein on 9 July with a force of around 60,000 men, including 20,000 cavalry, to face the advancing Ottoman army of over 100,000 commanded by the Grand Vizier, Damad Ali Pasha. Damad had successfully ejected the Venetians from the Morea and had a reputation as a competent commander.

By early August the Ottomans had reached Peterwardein following a cavalry clash with Count Palffy and constructed a hasty defensive position. Rather than allow the Ottomans to wear themselves out on Peterwardein’s modern defences he decided to take the offensive on 5 August. He feared the demoralising effect on his troops of a long period of inactivity and the cavalry skirmish confirmed his view of the technical superiority of his army.

Eugene deployed his army with one flank on the Danube and the other on the fortifications utilising old entrenchments thrown up in 1695. His infantry centre was commanded by Starhemberg supported by a second line under Bevern and a reserve under Loffelholz. On the more open left flank were six infantry battalions commanded by Prince Alexander of Wurtemberg and the cavalry led by Palffy. The smaller right flank consisted of four regiments commanded by Ebergenyi in boggy ground unsuitable for cavalry. A fierce storm damaged the Danube bridges and this delayed the Imperial deployment allowing the Ottomans time to react. The Ottoman cavalry deployed opposite the Austrian cavalry with the janissaries in the centre. The remaining troops skirmished through the morass on the Ottoman left.

Wurtemburg began the battle by advancing the left wing infantry and capturing the Ottoman gun positions. Palffy’s cavalry then charged the Ottoman horse driving them from the field. However, the centre made slower progress held up by small defensive positions. The Janissaries then counter attacked and pushed Starhemberg back to his start line that, even supported by Bevern’s second line, was barely holding. Eugene then ordered Wurtemburg to wheel right and take the exposed Ottoman centre in the flank while he sent the reserve under Loffelholz to secure the centre. The Ottoman cavalry pushed back by Palffy were unable to support this flank. The Janissaries lost hope and even a desperate charge by Damad Ali Pasha, in which he was killed, failed to rally his troops.

The Austrians lost over 3000 men and the Ottomans more than double that including the Grand Vizier. The Ottoman camp with its rich booty and 172 cannon was captured. Eugene pressed on quickly to besiege Temesvar an essential stage towards the ultimate goal of capturing Belgrade.

The Battle of Belgrade

In 1717 boosted by additional mercenary troops, Bavarians (and 45 princely volunteers) from Germany the 100,000 strong Imperial forces besieged Belgrade. By June Belgrade and its 30,000 garrison commanded by Mustapha Pasha was encircled although there was an active defence with sorties on land and by boats on the Danube. The Imperial Lines were to the south of the city filling in the triangle occupied by the city between the Danube and the Sava. The Ottoman relief army allegedly 200,000 strong under the command of the Grand Vizier Halil Pasha itself encircled the besiegers from the high ground. Halil bombarded the Imperial army which was brought close to collapse mainly from dysentery.

Eugene therefore decided to break out on 16 August with his weakened forces now numbering around 60,000 men. The infantry centre was commanded by Prince Alexander of Wurtemberg supported by Starhemberg and Prince Bevern. The cavalry wings by John Palffy supported by Ebergenyi and Mercy on the right and Montecucculi and Martigny on the left. Count Seckendorff commanded the reserve.

In the early hours Eugene advanced with his cavalry and infantry interspersed to maintain a steady firepower advance. A mist confused both sides and Eugene’s right wing cavalry led by Palffy blundered into some new Ottoman trenches. This raised the alarm and the Spahis counterattacked. However, Eugene reinforced the right with Mercy’s second line before they could be isolated. He then directed the main attack on the Ottoman centre. Despite heavy casualties from the Ottoman batteries Starhemberg’s infantry, coming out of the mist, captured the position at bayonet point. The only risk came from a gap between the right wing cavalry and the centre. An Ottoman division advanced on the gap but hesitated because of the mist. When it cleared Eugene plugged the gap with the Bevern’s second line and brought cavalry to hit the Ottoman flank. One battery remained supported by the Janissaries but they were driven off by grenadiers and foot flanked by cavalry.

The Ottomans lost 20,000 men and the Austrians suffered over 5,000 casualties. The victory was celebrated across Europe. A poem published in London included the words; To sign the Brother Chief, and make Eugene In equal lustre with great Marlboro’ shine.

Two days later the Fortress capitulated and a further relief army withdrew to the Banat. Imperial troops raided into Serbia during the winter and Tartars and Moldavians counter raided into Transylvania and Hungary. By 1718 all sides were ready for peace and the Treaty of Passarowitz in May 1918 confirmed the existing position with Venice losing the Morea and the Austrians retaining their advances in Bosnia, Croatia, the Banat, Walachia and of course Belgrade. Eugene’s Balkan campaigns had halted Ottoman expansion for good.

In 1717 boosted by additional mercenary troops, Bavarians (and 45 princely volunteers) from Germany the 100,000 strong Imperial forces besieged Belgrade. By June Belgrade and its 30,000 garrison commanded by Mustapha Pasha was encircled although there was an active defence with sorties on land and by boats on the Danube. The Imperial Lines were to the south of the city filling in the triangle occupied by the city between the Danube and the Sava. The Ottoman relief army allegedly 200,000 strong under the command of the Grand Vizier Halil Pasha itself encircled the besiegers from the high ground. Halil bombarded the Imperial army which was brought close to collapse mainly from dysentery.

Eugene therefore decided to break out on 16 August with his weakened forces now numbering around 60,000 men. The infantry centre was commanded by Prince Alexander of Wurtemberg supported by Starhemberg and Prince Bevern. The cavalry wings by John Palffy supported by Ebergenyi and Mercy on the right and Montecucculi and Martigny on the left. Count Seckendorff commanded the reserve.

In the early hours Eugene advanced with his cavalry and infantry interspersed to maintain a steady firepower advance. A mist confused both sides and Eugene’s right wing cavalry led by Palffy blundered into some new Ottoman trenches. This raised the alarm and the Spahis counterattacked. However, Eugene reinforced the right with Mercy’s second line before they could be isolated. He then directed the main attack on the Ottoman centre. Despite heavy casualties from the Ottoman batteries Starhemberg’s infantry, coming out of the mist, captured the position at bayonet point. The only risk came from a gap between the right wing cavalry and the centre. An Ottoman division advanced on the gap but hesitated because of the mist. When it cleared Eugene plugged the gap with the Bevern’s second line and brought cavalry to hit the Ottoman flank. One battery remained supported by the Janissaries but they were driven off by grenadiers and foot flanked by cavalry.

The Ottomans lost 20,000 men and the Austrians suffered over 5,000 casualties. The victory was celebrated across Europe. A poem published in London included the words; To sign the Brother Chief, and make Eugene In equal lustre with great Marlboro’ shine.

Two days later the Fortress capitulated and a further relief army withdrew to the Banat. Imperial troops raided into Serbia during the winter and Tartars and Moldavians counter raided into Transylvania and Hungary. By 1718 all sides were ready for peace and the Treaty of Passarowitz in May 1918 confirmed the existing position with Venice losing the Morea and the Austrians retaining their advances in Bosnia, Croatia, the Banat, Walachia and of course Belgrade. Eugene’s Balkan campaigns had halted Ottoman expansion for good.

The Armies

Whilst Eugene’s command achievements were considerable the superiority of the army he led owed more to the work of Raymond Montecuccoli. He improved mobility with smaller battalions and increased firepower by reducing the proportion of pikes. This work was continued after his death with the introduction of flintlocks with plug, ring and socket bayonet before most other western armies including the French. The Imperial forces in the Balkans also relied more heavily on light field artillery and up to a third of the army was cavalry. Dragoons (including Eugene’s early command) providing firepower (often on foot) with cuirassiers for shock action. The hussars who were mainly Croats as Hungary was in revolt for most of this period were used for raiding and scouting. A vital counter to the Ottoman Tartar horsemen.

The Ottoman armies of this period were not radically different tactically from the highpoint of Ottoman expansion. Light troops sought to goad the Imperial troops from their defensive position onto the Janissaries and the heavy artillery. However, the quality of the army had declined. The Janissaries were no longer the disciplined force of the previous century and economic pressures had undermined the Timar system and with it the Sipahis. The provincial Seratculi infantry were excellent skirmishers well suited for the endemic border warfare, but of limited value on the battlefield. The main problem was simply that the army had not adopted the advances in fire discipline which gave the Imperial army its vital cutting edge.

Wargaming

There are no shortage of figures for these campaigns. Malburian ranges provide most of the Imperial troops which also included the distinctive Bavarians. The Editor's collection used in the GDWS display games come mostly from the Foundry and Front Rank ranges. Ottoman forces are more likely to be found in renaissance ranges although remember that the Sipahis had little armour in this period. The Editor's 25mm army is based on the Dixon range (they also do a 15mm range) which is designed specifically for the period supplemented by Old Glory and Essex figures

The Battlefields Today

In recent years the Editor has visited both the Transylvanian and (what is now) Serbian battlefields of these campaigns. Whilst the 20th century has inevitably made its mark you can still get a feel for the period. A key feature of the late 17th century River Tisza area was the swampland either side of the river and the effect this had on campaigning. Today this has been drained but an essential visit is the fortress of Peterwardein (Petrovaradin) in its dramatic site above the Danube. A local group of enthusiasts have done much to promote the site.

Sources and Further Reading

Four biographies of Eugene were consulted for this article. The best in the Editor's opinion is Prince Eugene of Savoy by Derek McKay (1977). Nicholas Henderson’s Prince Eugen of Savoy (1964) is also good on the military aspects of his life. Colonel Malleson’s 1888 work and the probably forged (but still accurate and with a good period feel) Memoirs of Prince Eugene are available from Pallas Armata.

For an overview of the military history see Europe’s Steppe Frontier 1500-1800 by William McNeill (1964) and Gunther Rothenberg The Austrian Military Border in Croatia 1522-1747. For a diplomatic view of the period see Austria’s Eastern Question 1700-1790 by Karl Roider (1982). For the armies Raider Books publish C.A.Sapherson’s works on the Imperial armies and John Wilson on the Bavarians. There are excellent Osprey’s on the Ottoman armies and the Janissaries together with Godfrey Goodwin The Janissaries (1994). Richard Watts has also published a useful booklet The Ottoman Turkish Army in the 18th Century (Agema 1997).

See also Austria's Wars of Emergence 1683-1797 by Michael Hochedlinger for an overview of the campaigns and a detailed description of the Austrian army organisation. In particular the importance of logistics in the Balkans.

For an eye witness view of the area in the general period see Marsigli's Europe by John Stoye.

In recent years the Editor has visited both the Transylvanian and (what is now) Serbian battlefields of these campaigns. Whilst the 20th century has inevitably made its mark you can still get a feel for the period. A key feature of the late 17th century River Tisza area was the swampland either side of the river and the effect this had on campaigning. Today this has been drained but an essential visit is the fortress of Peterwardein (Petrovaradin) in its dramatic site above the Danube. A local group of enthusiasts have done much to promote the site.

Sources and Further Reading

Four biographies of Eugene were consulted for this article. The best in the Editor's opinion is Prince Eugene of Savoy by Derek McKay (1977). Nicholas Henderson’s Prince Eugen of Savoy (1964) is also good on the military aspects of his life. Colonel Malleson’s 1888 work and the probably forged (but still accurate and with a good period feel) Memoirs of Prince Eugene are available from Pallas Armata.

For an overview of the military history see Europe’s Steppe Frontier 1500-1800 by William McNeill (1964) and Gunther Rothenberg The Austrian Military Border in Croatia 1522-1747. For a diplomatic view of the period see Austria’s Eastern Question 1700-1790 by Karl Roider (1982). For the armies Raider Books publish C.A.Sapherson’s works on the Imperial armies and John Wilson on the Bavarians. There are excellent Osprey’s on the Ottoman armies and the Janissaries together with Godfrey Goodwin The Janissaries (1994). Richard Watts has also published a useful booklet The Ottoman Turkish Army in the 18th Century (Agema 1997).

See also Austria's Wars of Emergence 1683-1797 by Michael Hochedlinger for an overview of the campaigns and a detailed description of the Austrian army organisation. In particular the importance of logistics in the Balkans.

For an eye witness view of the area in the general period see Marsigli's Europe by John Stoye.