- Home

- About

-

Travel

-

Features

- Dyrrachion1081

- Normans in the Balkans

- Manolada 1316

- Kosovo 1389

- Castles on the Danube

- Late Medieval Bosnian Army

- Doboj 1415

- Wallachian and Moldovan troops of the Napoleonic wars

- Anchialos 917

- Slovenian Borderlands

- The Zadruga and the Military Border

- Cretan War in the Adriatic

- Salonika 1916

- Uskoks of Senj

- Siege of Klis 1537

- Eugene in the Balkans

- Moldavian Surprise 1711

- Austro-Turkish War 1737-9

- Militargrenze

- Invading Ottoman Turkey

- Siege of Ragusa 1814

- Russo-Turkish War 1806-12

- Serbian Uprising 1815

- Ali Pasha

- Ottoman Army 1826

- Aleksinac 1876

- Shipka Pass

- Slivnitsa 1885

- Romanian Army 1878

- Austrian forts 19thC

- Kumanovo 1912

- Catalca Lines

- Adrianople 1912-13

- Kajmakcalan 1916

- The other 1918 campaign

- Macedonia air war WW1

- War of the Stray Dog

- Royal Yugoslavian armed forces

- Blunder in the Mountains

- Romanian SS

- Gebirgsjager in the Balkans

- Knights Move 1944

- Vis during WW2

- HLI in the Adriatic

- Adriatic Cruel Seas

- Dalmatian Bridgehead

- Cyprus 1974

- Transnistrian War

- Ottoman Navy Napoleonic wars

- Medieval Balkans

- Balkan lockdown quiz >

- Reviews

-

Armies

- Ancient Greeks

- Pyrrhic army of Epirus

- Dacian wars

- Goths

- Late Roman

- Comnenan Byzantine Army

- Normans

- Serbian medieval

- Albanian medieval

- Wallachian medieval

- Bosnian Medieval

- Catalan Company

- Polish 17C

- Austrian Imperialist

- Ottoman

- Austrian 18thC

- Russian Early 18thC

- Ottoman Napoleonic

- Greek Revolution

- 1848 Hungarian Revolution

- Russian Crimean war

- Romanian Army of 1877

- Ottoman 1877

- Russian 1877

- Balkan Wars 1912-13

- Macedonia WW1

- Greece WW2

- Italian Army WW2

- Gebirgsjager WW2

- Hungary WW2

- Turkey WW2

- Soviet Union WW2

- Bulgaria WW2

- Turkish Korean War Brigade

- Balkan Wars 1990s

- Links

- Books

Slovenian Borderlands

When we think of Balkan borderlands, the Military border between the Habsburgs and Ottomans in modern-day Croatia (Militärgrenze) comes to mind. That was formally established in 1553. However, there was an earlier border area in modern-day Slovenia. Not to be confused with the later (1776) Slavonian Military Frontier, mostly in eastern Croatia and northern Serbia.

In the later Middle Ages, Slovenia was sparsely populated, reflecting the mountainous and wooded terrain. The population of the modern capital Ljubljana numbered no more than 5000 by the early sixteenth century. Despite its limited economic value, it was strategically important to the Holy Roman Empire (Habsburg dominated by the end of the 13th century), giving them access to the sea and acting as a buffer against the Kingdom of Hungary to the east and, more importantly, the Ottoman Empire to the south.

Militarily this led to the development of several hundred castles, many more than could be justified by the region's economy. Even today, you can see castle ruins and remains on the top of steep hills in the country. Between the 11th and 14th centuries, feudal families, such as the Dukes of Spanheim, the Counts of Gorizia, the Counts of Celje, led the consolidation of lands in the region. Troops from the area also served as mercenaries in Italy, which led to a transition from feudal levies to professional retinues of men-at-arms and mounted crossbowmen. Slovenian troops were present at the Siege of Zadar (1346) and Nicopolis (1396). Ambitious counts like Ulrich II attempted to carve out an independent kingdom but were forced to accept Habsburg suzerainty by 1500.

In the later Middle Ages, Slovenia was sparsely populated, reflecting the mountainous and wooded terrain. The population of the modern capital Ljubljana numbered no more than 5000 by the early sixteenth century. Despite its limited economic value, it was strategically important to the Holy Roman Empire (Habsburg dominated by the end of the 13th century), giving them access to the sea and acting as a buffer against the Kingdom of Hungary to the east and, more importantly, the Ottoman Empire to the south.

Militarily this led to the development of several hundred castles, many more than could be justified by the region's economy. Even today, you can see castle ruins and remains on the top of steep hills in the country. Between the 11th and 14th centuries, feudal families, such as the Dukes of Spanheim, the Counts of Gorizia, the Counts of Celje, led the consolidation of lands in the region. Troops from the area also served as mercenaries in Italy, which led to a transition from feudal levies to professional retinues of men-at-arms and mounted crossbowmen. Slovenian troops were present at the Siege of Zadar (1346) and Nicopolis (1396). Ambitious counts like Ulrich II attempted to carve out an independent kingdom but were forced to accept Habsburg suzerainty by 1500.

The leading opponent of Habsburg rule was the Counts of Celje. The rise of this family from central Slovenia began in the later 14th century, and they became one of the most powerful families in the Balkans. They were related by marriage with rulers of Bosnia as well as Polish and Hungarian kings. In 1396 Count Hermann II of Celje saved the Hungarian king (later Holy Roman Emperor) Sigismund of Luxemburg at the Battle of Nicopolis. A strong bond was strengthened when Sigismund married Hermann's daughter Barbara, and in 1446 they were elevated to Dukes. A dispute with the Habsburg Duke Frederick V led to a prolonged conflict that devastated the region between 1436 and 1443. Frederick captured Celje and gained all their possessions after a deal with the widow of the last Duke.

From 1469 the Slovenian lands were subjected to constant raiding by Ottoman forces based in Bosnia, even though they were away from the main Ottoman invasion route. As many as 200,000 local inhabitants had been killed or taken into captivity by the early sixteenth century, not helped by conflicts with Venice and Hungary. The ruling elites essentially held out in the mountain castles while the peasants built stone walls around churches. Maximilian I initiated reforms that included armouries throughout his provinces. Inventory records from the early sixteenth century indicate that Slovenian territory had sufficient crossbows and polearms to equip a force of at least 10,000 men.

From 1469 the Slovenian lands were subjected to constant raiding by Ottoman forces based in Bosnia, even though they were away from the main Ottoman invasion route. As many as 200,000 local inhabitants had been killed or taken into captivity by the early sixteenth century, not helped by conflicts with Venice and Hungary. The ruling elites essentially held out in the mountain castles while the peasants built stone walls around churches. Maximilian I initiated reforms that included armouries throughout his provinces. Inventory records from the early sixteenth century indicate that Slovenian territory had sufficient crossbows and polearms to equip a force of at least 10,000 men.

|

This was impressively large for the period, given the small population. There were few original military formations with the South German model adopted throughout the Habsburg Eastern Alps, albeit with some Italian influence and lighter armour suited for border warfare. They were also an early adopter of firearms and later Swiss pike formations and Lansknechts.

More than 130 rebellions occurred in Slovenia, spanning from the 13th to the 17th century, probably more than any other place in Europe. In 1515, a peasant revolt spread across Slovene territory, with some 80,000 rebels participating. The rebellion was put down by the mercenaries of the Holy Roman Empire, with the deciding battle fought at Celje. There were further revolts in 1572 and 1573, which wrought havoc throughout the wider region. |

On the other side of the hill, the Ottomans began to consolidate their Empire during this period. After capturing Constantinople, the Ottomans turned their attention to Bosnia, where the locals engaged in civil war. The Serbian vassal state was supported in their claim for Srebrenica, and the Ottomans stepped up their attacks on Bosnia, establishing Vrhbosna (Sarajevo) as their main base. A major invasion in 1463 captured key Bosnian fortresses, and the Bosnian king capitulated with some Bosnian nobles entering Ottoman service.

This led to raids into Croatia, which reached as far as Kranj in Slovenia. Christian disunity between Hungary, Venice and the local nobles aided the Ottomans, with increasing numbers of Croatian nobles turning to the Ottomans. This allowed raiders free passage to attack further north. The Battle of Mohacs in 1526 consolidated the Ottoman victories and annexed all of Srem and the plains of Slavonia. By 1528 the Ottomans held a line from the south of Senj to Karlovac, Sisak and Bjelovar.

These conquests meant the Ottomans began to take fortifications more seriously, if only as a base for offensive operations. The extraordinary growth of the Empire had been achieved without the large scale use of fortifications. Even the famous ones cutting off the Straits were not followed up. They demolished some Byzantine fortresses in the Balkans but strengthened some on their northern frontier. In particular, on the Danube at Silistria, Nikopol and Vidin. Coastal fortifications were also more likely to be maintained than the more fluid land border.

This led to raids into Croatia, which reached as far as Kranj in Slovenia. Christian disunity between Hungary, Venice and the local nobles aided the Ottomans, with increasing numbers of Croatian nobles turning to the Ottomans. This allowed raiders free passage to attack further north. The Battle of Mohacs in 1526 consolidated the Ottoman victories and annexed all of Srem and the plains of Slavonia. By 1528 the Ottomans held a line from the south of Senj to Karlovac, Sisak and Bjelovar.

These conquests meant the Ottomans began to take fortifications more seriously, if only as a base for offensive operations. The extraordinary growth of the Empire had been achieved without the large scale use of fortifications. Even the famous ones cutting off the Straits were not followed up. They demolished some Byzantine fortresses in the Balkans but strengthened some on their northern frontier. In particular, on the Danube at Silistria, Nikopol and Vidin. Coastal fortifications were also more likely to be maintained than the more fluid land border.

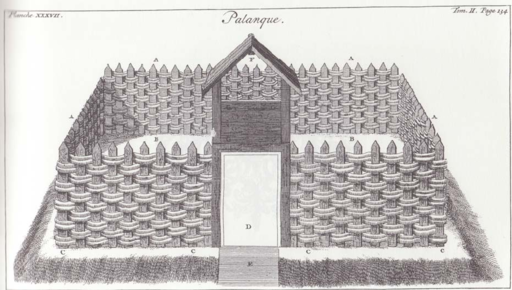

On the Slavonian frontier, fortified places developed along the frontier and the main communication routes. The Sultan appointed a senior commander (Aga), and he would nominate local commanders (Kethüda yeri). Konstantin Mihailovic, a Slav soldier serving as a Janissary in the mid-fifteenth century, refers to the 'emperor' (Sultan) holding the fortresses in his own hands rather than passing them onto lords, and garrisoning them with janissaries and gönüllü (volunteers). He describes the fort as being commanded by a Dyzdar (or Disdar) supported by a Kethaya (Kethüda) and then sub-commanders called Bulukbasse (Bölük basis). The sipahi would be allocated timar fiefs in the surrounding area, and some would serve in the fortresses. Probably for security reasons, these sipahi would initially come from Anatolia, but locally recruited troops were increasingly used. The forts were typically earth and timber palankas rather than stone castles.

Raiding was undertaken mainly by Akinci (raiders), the light cavalry who could be the Muslim gazis of the early Ottoman period or later recruits. As with many borderlands, small scale warfare continued even during periods of official peace. They were less interested in capturing fortresses than booty and slaves. This was a way of life that would continue even when the military frontier became more settled.

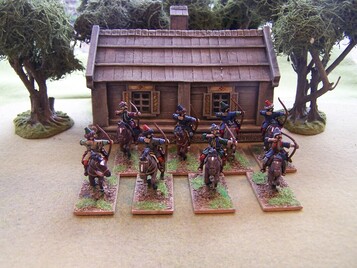

For the wargamer, this period offers plenty of opportunities to play skirmish or small battle games. Saga and Lion Rampant rules are particularly suitable. Scenarios with local Slavonian forces defending a village against Ottoman raiders or even counter-attacks on the Ottomans escorting their booty back to the border.

Raiding was undertaken mainly by Akinci (raiders), the light cavalry who could be the Muslim gazis of the early Ottoman period or later recruits. As with many borderlands, small scale warfare continued even during periods of official peace. They were less interested in capturing fortresses than booty and slaves. This was a way of life that would continue even when the military frontier became more settled.

For the wargamer, this period offers plenty of opportunities to play skirmish or small battle games. Saga and Lion Rampant rules are particularly suitable. Scenarios with local Slavonian forces defending a village against Ottoman raiders or even counter-attacks on the Ottomans escorting their booty back to the border.

Further reading:

Babinger, F, Mehmed the Conqueror and his Time (Princeton, 1978)

Engel, P, The Realm of St Stephen 895-1526 (I.B.Tauris 2005)

Fine, J, The Late Medieval Balkans (Michigan Press, 1994)

Lazar, T, At the Crossroads of Empires, (Medieval Warfare XI-1)

Mihailovic, K, Mémoires of a Janissary (Ann Arbor, 1975)

Nicolle, David, Cross and crescent in the Balkans (Pen and Sword, 2010)

Shaw, S, The History of the Ottoman Empire, Volume 1 (Cambridge 1975)

Stavrianos, L, The Balkans since 1453 (Hurst, 2000)

Babinger, F, Mehmed the Conqueror and his Time (Princeton, 1978)

Engel, P, The Realm of St Stephen 895-1526 (I.B.Tauris 2005)

Fine, J, The Late Medieval Balkans (Michigan Press, 1994)

Lazar, T, At the Crossroads of Empires, (Medieval Warfare XI-1)

Mihailovic, K, Mémoires of a Janissary (Ann Arbor, 1975)

Nicolle, David, Cross and crescent in the Balkans (Pen and Sword, 2010)

Shaw, S, The History of the Ottoman Empire, Volume 1 (Cambridge 1975)

Stavrianos, L, The Balkans since 1453 (Hurst, 2000)