- Home

- About

-

Travel

-

Features

- Dyrrachion1081

- Normans in the Balkans

- Manolada 1316

- Kosovo 1389

- Castles on the Danube

- Late Medieval Bosnian Army

- Doboj 1415

- Wallachian and Moldovan troops of the Napoleonic wars

- Anchialos 917

- Slovenian Borderlands

- The Zadruga and the Military Border

- Cretan War in the Adriatic

- Salonika 1916

- Uskoks of Senj

- Siege of Klis 1537

- Eugene in the Balkans

- Moldavian Surprise 1711

- Austro-Turkish War 1737-9

- Militargrenze

- Invading Ottoman Turkey

- Siege of Ragusa 1814

- Russo-Turkish War 1806-12

- Serbian Uprising 1815

- Ali Pasha

- Ottoman Army 1826

- Aleksinac 1876

- Shipka Pass

- Slivnitsa 1885

- Romanian Army 1878

- Austrian forts 19thC

- Kumanovo 1912

- Catalca Lines

- Adrianople 1912-13

- Kajmakcalan 1916

- The other 1918 campaign

- Macedonia air war WW1

- War of the Stray Dog

- Royal Yugoslavian armed forces

- Blunder in the Mountains

- Romanian SS

- Gebirgsjager in the Balkans

- Knights Move 1944

- Vis during WW2

- HLI in the Adriatic

- Adriatic Cruel Seas

- Dalmatian Bridgehead

- Cyprus 1974

- Transnistrian War

- Ottoman Navy Napoleonic wars

- Medieval Balkans

- Balkan lockdown quiz >

- Reviews

-

Armies

- Ancient Greeks

- Pyrrhic army of Epirus

- Dacian wars

- Goths

- Late Roman

- Comnenan Byzantine Army

- Normans

- Serbian medieval

- Albanian medieval

- Wallachian medieval

- Bosnian Medieval

- Catalan Company

- Polish 17C

- Austrian Imperialist

- Ottoman

- Austrian 18thC

- Russian Early 18thC

- Ottoman Napoleonic

- Greek Revolution

- 1848 Hungarian Revolution

- Russian Crimean war

- Romanian Army of 1877

- Ottoman 1877

- Russian 1877

- Balkan Wars 1912-13

- Macedonia WW1

- Greece WW2

- Italian Army WW2

- Gebirgsjager WW2

- Hungary WW2

- Turkey WW2

- Soviet Union WW2

- Bulgaria WW2

- Turkish Korean War Brigade

- Balkan Wars 1990s

- Links

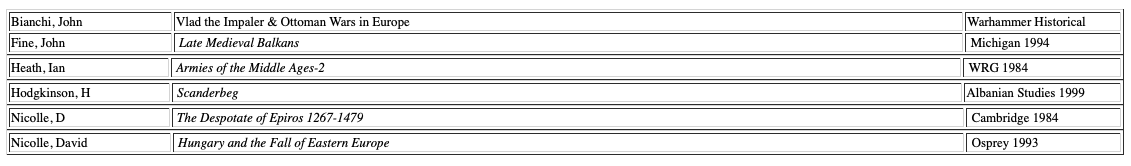

- Books

Albanian medieval

Southern Albania and Epirus remained under Byzantine domination till 1204, when, after the capture of Constantinople by the crusaders, Michael Comnenus, a member of the imperial family, withdrew to Epirus and founded an independent sovereignty known as the Despotate of Epirus at Iannina; his realm included the whole of southern Albania, Acarnania and Aetolia. Meanwhile Durazzo, with Berat and Central Albania, had passed into the hands of the Sicilian kings of the house of Anjou, who ruled these regions, which they styled the "Kingdom of Albania," from 1271 to 1368, maintaining a constant warfare with the Byzantine emperors.

The Serbians installed themselves in Upper Albania about 1180, and the provinces of Scutari and Prizren were ruled by kings of the house of Nemanya till 1360; Stefan Dushan (1331-1358), the greatest of these monarchs, included all Albania in his extensive but short-lived empire.

After the death of Dushan and the break-up of the Serbian empire, a new epoch began when Albania fell under the rule of chieftains more or less of native origin. A portion of Upper Albania was ruled by the Balsha dynasty (1366-1421) and embraced Catholicism. Alessio and a tract of the interior in the direction of Ipek was governed by the Dukajin. The northern portion of the "kingdom of Albania," including Durazzo and Kroia, was ruled by the family of Thopia (1359-1392) and afterwards by that of Lastriota, to which Scanderbeg belonged; the southern portion with Berat, by the Musaki (1368--1476).

The Serbians installed themselves in Upper Albania about 1180, and the provinces of Scutari and Prizren were ruled by kings of the house of Nemanya till 1360; Stefan Dushan (1331-1358), the greatest of these monarchs, included all Albania in his extensive but short-lived empire.

After the death of Dushan and the break-up of the Serbian empire, a new epoch began when Albania fell under the rule of chieftains more or less of native origin. A portion of Upper Albania was ruled by the Balsha dynasty (1366-1421) and embraced Catholicism. Alessio and a tract of the interior in the direction of Ipek was governed by the Dukajin. The northern portion of the "kingdom of Albania," including Durazzo and Kroia, was ruled by the family of Thopia (1359-1392) and afterwards by that of Lastriota, to which Scanderbeg belonged; the southern portion with Berat, by the Musaki (1368--1476).

In the middle of the 14th century a great migration of Albanians from the mountainous districts of the north took place, under the chiefs Jin Bua Spata and Peter Liosha; they advanced southwards as far as Acarnania and Aetolia (1358), occupied the greater portion of the despotate of Epirus, and took Iannina and Arta. In the latter half of the century large colonies of Tosks were planted in the Morea by the despots of Mistra, and in Attica and Boeotia by Luke Nerio of Athens. As the power of the Balshas declined, the Venetians towards the close of the 14th century established themselves at Scutari, Budua, Antivari and elsewhere in northern Albania.

In 1389 a coalition of Balkan forces including Albanians, led by Prince Lazar of Serbia, met the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Kosovo.

The Ottomans under Mehmet I swept into Albania and by 1417 had captured the main towns and established Ottoman rule. The Venetians still held many of the important coastal ports. Warfare continued led by the most important clan chieftain Gjon Kastrioti. His son Gjergi was sent as a hostage to the Sultan’s court, converted to Islam with the name of Skender. He rose to the rank of Beg before deserting and joining the revolt. Skenderbeg as he became known succeeded in partially uniting the Albanian tribes for the first time. For 25 years he led forces which rarely exceeded 10,000 in a series of victories against larger Ottoman armies. Most famously at Torviolli (1444) when he trapped 25,000 Ottomans under Ali Pasha and Abulena (1457) when he scattered an army of up to 80,000 Turks.

Skanderbeg’s resistance was widely admired in western Europe and he received some supplies and troops from Venice and Naples. By 1466 superior numbers began to take there toll on Albanian manpower. Sultan Mehmet II captured Kruja with an army reputed to be 150,000 strong. Skenderbeg died two years later and resistance finally ended in 1479.

Though now lacking Skanderbeg's leadership, the Albanians remained troublesome enough to provoke the Turks into a concerted effort to Islamize the population and some two thirds of the population did so. However, this did not achieve the desired effect; the Ottoman government never exercised full control over Albania. Although some Albanians rose to positions of prominence within the empire, including that of Grand Vizier, others, particularly those in the highlands, did not pay taxes, serve in the army, or surrender their arms.

Albanian armies were based on native light cavalry that became known as Stradiots, supported by infantry. Their guerrilla style tactics made them difficult to pin down in the Albanian highlands. Armies from the costal regions would be more conventional with heavy infantry, crossbows and mercenary Italian knights.

In 1389 a coalition of Balkan forces including Albanians, led by Prince Lazar of Serbia, met the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Kosovo.

The Ottomans under Mehmet I swept into Albania and by 1417 had captured the main towns and established Ottoman rule. The Venetians still held many of the important coastal ports. Warfare continued led by the most important clan chieftain Gjon Kastrioti. His son Gjergi was sent as a hostage to the Sultan’s court, converted to Islam with the name of Skender. He rose to the rank of Beg before deserting and joining the revolt. Skenderbeg as he became known succeeded in partially uniting the Albanian tribes for the first time. For 25 years he led forces which rarely exceeded 10,000 in a series of victories against larger Ottoman armies. Most famously at Torviolli (1444) when he trapped 25,000 Ottomans under Ali Pasha and Abulena (1457) when he scattered an army of up to 80,000 Turks.

Skanderbeg’s resistance was widely admired in western Europe and he received some supplies and troops from Venice and Naples. By 1466 superior numbers began to take there toll on Albanian manpower. Sultan Mehmet II captured Kruja with an army reputed to be 150,000 strong. Skenderbeg died two years later and resistance finally ended in 1479.

Though now lacking Skanderbeg's leadership, the Albanians remained troublesome enough to provoke the Turks into a concerted effort to Islamize the population and some two thirds of the population did so. However, this did not achieve the desired effect; the Ottoman government never exercised full control over Albania. Although some Albanians rose to positions of prominence within the empire, including that of Grand Vizier, others, particularly those in the highlands, did not pay taxes, serve in the army, or surrender their arms.

Albanian armies were based on native light cavalry that became known as Stradiots, supported by infantry. Their guerrilla style tactics made them difficult to pin down in the Albanian highlands. Armies from the costal regions would be more conventional with heavy infantry, crossbows and mercenary Italian knights.