- Home

- About

-

Travel

-

Features

- Dyrrachion1081

- Normans in the Balkans

- Manolada 1316

- Kosovo 1389

- Castles on the Danube

- Late Medieval Bosnian Army

- Doboj 1415

- Wallachian and Moldovan troops of the Napoleonic wars

- Anchialos 917

- Slovenian Borderlands

- The Zadruga and the Military Border

- Cretan War in the Adriatic

- Salonika 1916

- Uskoks of Senj

- Siege of Klis 1537

- Eugene in the Balkans

- Moldavian Surprise 1711

- Austro-Turkish War 1737-9

- Militargrenze

- Invading Ottoman Turkey

- Siege of Ragusa 1814

- Russo-Turkish War 1806-12

- Serbian Uprising 1815

- Ali Pasha

- Ottoman Army 1826

- Aleksinac 1876

- Shipka Pass

- Slivnitsa 1885

- Romanian Army 1878

- Austrian forts 19thC

- Kumanovo 1912

- Catalca Lines

- Adrianople 1912-13

- Kajmakcalan 1916

- The other 1918 campaign

- Macedonia air war WW1

- War of the Stray Dog

- Royal Yugoslavian armed forces

- Blunder in the Mountains

- Romanian SS

- Gebirgsjager in the Balkans

- Knights Move 1944

- Vis during WW2

- HLI in the Adriatic

- Adriatic Cruel Seas

- Dalmatian Bridgehead

- Cyprus 1974

- Transnistrian War

- Ottoman Navy Napoleonic wars

- Medieval Balkans

- Balkan lockdown quiz >

- Reviews

-

Armies

- Ancient Greeks

- Pyrrhic army of Epirus

- Dacian wars

- Goths

- Late Roman

- Comnenan Byzantine Army

- Normans

- Serbian medieval

- Albanian medieval

- Wallachian medieval

- Bosnian Medieval

- Catalan Company

- Polish 17C

- Austrian Imperialist

- Ottoman

- Austrian 18thC

- Russian Early 18thC

- Ottoman Napoleonic

- Greek Revolution

- 1848 Hungarian Revolution

- Russian Crimean war

- Romanian Army of 1877

- Ottoman 1877

- Russian 1877

- Balkan Wars 1912-13

- Macedonia WW1

- Greece WW2

- Italian Army WW2

- Gebirgsjager WW2

- Hungary WW2

- Turkey WW2

- Soviet Union WW2

- Bulgaria WW2

- Turkish Korean War Brigade

- Balkan Wars 1990s

- Links

- Books

Russo-Turkish War 1806-12

Introduction

This year (2012) is the 200th anniversary of Napoleon’s fateful invasion of Russia. No doubt much will be written about the 1812 campaign this year with vivid pictures of the terrible retreat from Moscow etc.

1812 is also the 200th anniversary of the Treaty of Bucharest that ended the Russo-Turkish War that had been raging intermittently since 1806. This treaty meant that Russian troops were free to join the main Russian armies facing Napoleon. Perhaps equally important they gained the services of Mikhail Kutuzov who was the Russian commander in the south. In most histories of the 1812 campaign the Treaty of Bucharest is presented as being almost forced on the Tsar in order for him to concentrate on the French. While it is true that the Russian’s settled for modest, but important gains from the Treaty, they were in a stronger position than is often appreciated.

The 1806 war

The war has to be seen in the context of four separate conflicts between Russia and the Ottoman Empire in the 18th Century. After Peter the Great’s near disaster early in the century the Russian’s were gaining the upper hand. The border had been advanced to the Dniester and Kuban rivers and the Ottoman’s had decided on a period of peace.

The Battle of Austerlitz changed the balance of power, bringing the French into the Balkans and the Ottoman’s moved into the French camp. The causus belli of the war was the prohibition of Russian ships from the Dardanelles and the dismissal of pro-Russian Hospodars (rulers) of Moldavia and Wallachia, contrary to treaty.

The war had three main periods. The early hostilities involved the Russian occupation of Moldavia and Wallachia and failed Ottoman offensives into Wallachia. The Russians also defeated the Ottomans at the Battle of Arpachai in Armenia. The second phase (1808-10) was a consequence of the Peace of Tilsit between the Tsar Alexander and Napoleon. This enabled the Russians to move troops south and launch attacks on the Danube fortresses from Bessarabia. A series of Russian commanders including Prozorovsky, Bagration, Kamensky and Langeron had a number of victories over the Ottomans, but made no decisive progress in the war.

As relations were becoming strained again with Napoleon, Alexander needed to conclude the conflict and recalled Kutuzov for the final stage of the war.

Enter Kutuzov – The 1811-12 campaign

Kutuzov was not Alexander’s favourite general after overruling him in 1805. However, he was respected by the army and had fought the Ottomans in both previous wars and served under Prozorovsky in 1809.

He started by evacuating the Danube fortress of Silistria drawing a much larger Ottoman army to defeat at the Battle at Ruse (20 June 1811). Kutuzov again withdrew over the Danube encouraging a new Ottoman army to follow him. With the largest portion of the Ottoman army across the river he sent a force of 7,500 cavalry and jagers over the river to capture the Ottoman camp and encircle them. Instead of starving the Ottomans into surrender he effectively used them as hostages to negotiate the Treaty of Bucharest. Students of the Russian 1812 campaign will see how Kutuzov developed his strategy.

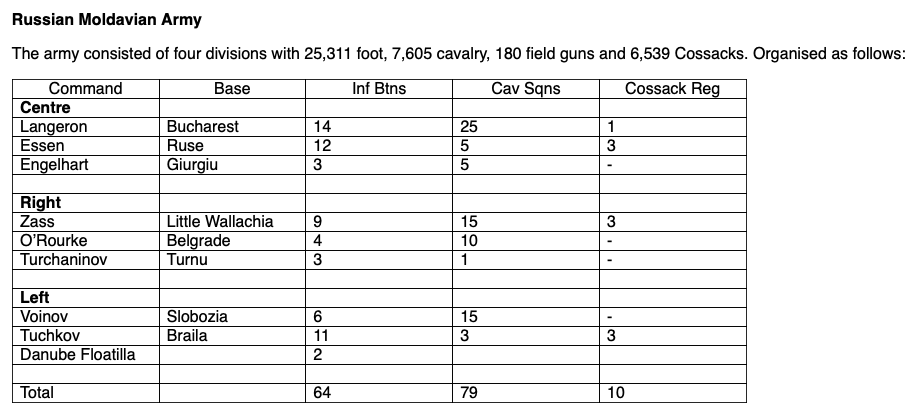

Russian Moldavian Army

The army consisted of four divisions with 25,311 foot, 7,605 cavalry, 180 field guns and 6,539 Cossacks. Organised as follows:

This year (2012) is the 200th anniversary of Napoleon’s fateful invasion of Russia. No doubt much will be written about the 1812 campaign this year with vivid pictures of the terrible retreat from Moscow etc.

1812 is also the 200th anniversary of the Treaty of Bucharest that ended the Russo-Turkish War that had been raging intermittently since 1806. This treaty meant that Russian troops were free to join the main Russian armies facing Napoleon. Perhaps equally important they gained the services of Mikhail Kutuzov who was the Russian commander in the south. In most histories of the 1812 campaign the Treaty of Bucharest is presented as being almost forced on the Tsar in order for him to concentrate on the French. While it is true that the Russian’s settled for modest, but important gains from the Treaty, they were in a stronger position than is often appreciated.

The 1806 war

The war has to be seen in the context of four separate conflicts between Russia and the Ottoman Empire in the 18th Century. After Peter the Great’s near disaster early in the century the Russian’s were gaining the upper hand. The border had been advanced to the Dniester and Kuban rivers and the Ottoman’s had decided on a period of peace.

The Battle of Austerlitz changed the balance of power, bringing the French into the Balkans and the Ottoman’s moved into the French camp. The causus belli of the war was the prohibition of Russian ships from the Dardanelles and the dismissal of pro-Russian Hospodars (rulers) of Moldavia and Wallachia, contrary to treaty.

The war had three main periods. The early hostilities involved the Russian occupation of Moldavia and Wallachia and failed Ottoman offensives into Wallachia. The Russians also defeated the Ottomans at the Battle of Arpachai in Armenia. The second phase (1808-10) was a consequence of the Peace of Tilsit between the Tsar Alexander and Napoleon. This enabled the Russians to move troops south and launch attacks on the Danube fortresses from Bessarabia. A series of Russian commanders including Prozorovsky, Bagration, Kamensky and Langeron had a number of victories over the Ottomans, but made no decisive progress in the war.

As relations were becoming strained again with Napoleon, Alexander needed to conclude the conflict and recalled Kutuzov for the final stage of the war.

Enter Kutuzov – The 1811-12 campaign

Kutuzov was not Alexander’s favourite general after overruling him in 1805. However, he was respected by the army and had fought the Ottomans in both previous wars and served under Prozorovsky in 1809.

He started by evacuating the Danube fortress of Silistria drawing a much larger Ottoman army to defeat at the Battle at Ruse (20 June 1811). Kutuzov again withdrew over the Danube encouraging a new Ottoman army to follow him. With the largest portion of the Ottoman army across the river he sent a force of 7,500 cavalry and jagers over the river to capture the Ottoman camp and encircle them. Instead of starving the Ottomans into surrender he effectively used them as hostages to negotiate the Treaty of Bucharest. Students of the Russian 1812 campaign will see how Kutuzov developed his strategy.

Russian Moldavian Army

The army consisted of four divisions with 25,311 foot, 7,605 cavalry, 180 field guns and 6,539 Cossacks. Organised as follows:

This force had to cover a front of 662 miles. However, Kutuzov had effectively bribed the Pasha of Vidin to secure his right flank and the Danube Floatilla protected his left, so his best troops with Langeron and Essen’s Corps were in the centre.

Sadly, we have no equivalent orbat for the Ottoman forces. All we know is that command of the army passed to Ahmed Bey and Bosnak Agha as his deputy. They mobilised 50,000 men at Shumla and 25,000 at Sofia by May, with more promised. This force included at least 6,000 Janissaries. They also had around 100 guns.

Russian tactics against the Ottomans usually involved forming regimental squares in at least two lines with cavalry in a third line. For example at Ruse, Kutuzov’s army formed into 6 (3 btn) squares in the first line, 3 squares in the second and his cavalry in a third line. Each square had battery guns as well as the two light guns attached to each battalion.

Sadly, we have no equivalent orbat for the Ottoman forces. All we know is that command of the army passed to Ahmed Bey and Bosnak Agha as his deputy. They mobilised 50,000 men at Shumla and 25,000 at Sofia by May, with more promised. This force included at least 6,000 Janissaries. They also had around 100 guns.

Russian tactics against the Ottomans usually involved forming regimental squares in at least two lines with cavalry in a third line. For example at Ruse, Kutuzov’s army formed into 6 (3 btn) squares in the first line, 3 squares in the second and his cavalry in a third line. Each square had battery guns as well as the two light guns attached to each battalion.

|

Further Reading

For a full description of the campaigns, albeit from a Russian perspective, we have the Russian Staff study by General Mikhailovsky-Danilevsky written in 1843. Thankfully translated by Alexander Mikaberidze as Russo-Turkish War of 1806-1812 and published by The Nafziger Collection in 2002. There is a further Russian study The War between Russia and Turkey 1806—1812 that I haven’t read. French policy is covered in Napoleon and the Dardanelles by Vernon Puryear (California Press 1951). The usual Ottoman histories (Jelavich, Shaw & Inalcik) give an overview of Ottoman policy. Uniform details in Osprey MAA 314 (Ottomans) and 185 & 189 (Russians). |