- Home

- About

-

Travel

-

Features

- Dyrrachion1081

- Normans in the Balkans

- Manolada 1316

- Kosovo 1389

- Castles on the Danube

- Late Medieval Bosnian Army

- Doboj 1415

- Wallachian and Moldovan troops of the Napoleonic wars

- Anchialos 917

- Slovenian Borderlands

- The Zadruga and the Military Border

- Cretan War in the Adriatic

- Salonika 1916

- Uskoks of Senj

- Siege of Klis 1537

- Eugene in the Balkans

- Moldavian Surprise 1711

- Austro-Turkish War 1737-9

- Militargrenze

- Invading Ottoman Turkey

- Siege of Ragusa 1814

- Russo-Turkish War 1806-12

- Serbian Uprising 1815

- Ali Pasha

- Ottoman Army 1826

- Aleksinac 1876

- Shipka Pass

- Slivnitsa 1885

- Romanian Army 1878

- Austrian forts 19thC

- Kumanovo 1912

- Catalca Lines

- Adrianople 1912-13

- Kajmakcalan 1916

- The other 1918 campaign

- Macedonia air war WW1

- War of the Stray Dog

- Royal Yugoslavian armed forces

- Blunder in the Mountains

- Romanian SS

- Gebirgsjager in the Balkans

- Knights Move 1944

- Vis during WW2

- HLI in the Adriatic

- Adriatic Cruel Seas

- Dalmatian Bridgehead

- Cyprus 1974

- Transnistrian War

- Ottoman Navy Napoleonic wars

- Medieval Balkans

- Balkan lockdown quiz >

- Reviews

-

Armies

- Ancient Greeks

- Pyrrhic army of Epirus

- Dacian wars

- Goths

- Late Roman

- Comnenan Byzantine Army

- Normans

- Serbian medieval

- Albanian medieval

- Wallachian medieval

- Bosnian Medieval

- Catalan Company

- Polish 17C

- Austrian Imperialist

- Ottoman

- Austrian 18thC

- Russian Early 18thC

- Ottoman Napoleonic

- Greek Revolution

- 1848 Hungarian Revolution

- Russian Crimean war

- Romanian Army of 1877

- Ottoman 1877

- Russian 1877

- Balkan Wars 1912-13

- Macedonia WW1

- Greece WW2

- Italian Army WW2

- Gebirgsjager WW2

- Hungary WW2

- Turkey WW2

- Soviet Union WW2

- Bulgaria WW2

- Turkish Korean War Brigade

- Balkan Wars 1990s

- Links

- Books

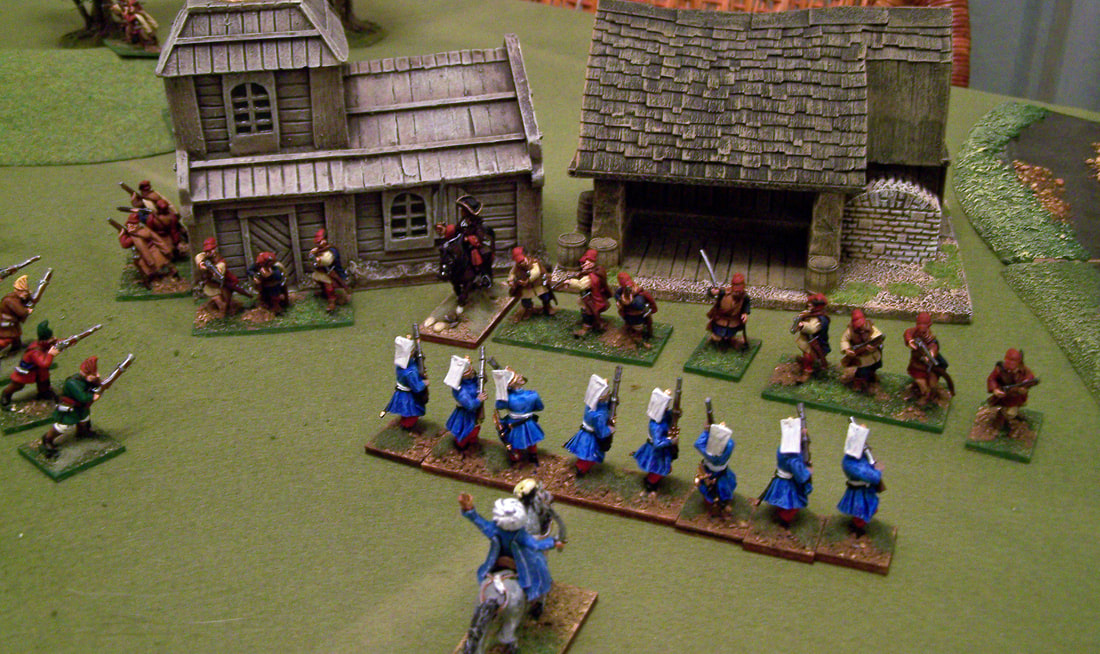

The Military Border between Croatia and Bosnia

In this article I will examine the military border between Croatia and Bosnia as the basis for an adaptation of the popular rule set ‘Muskets and Tomahawks’ to wargame the period.

The Militargrenze

The Habsburgs maintained a military zone, the Militargrenze, along Croatia’s southern border for over 350 years, from 1522 to 1881. The original purpose was a defensive screen against Ottoman incursions. Later it became an important Habsburg military institution, fighting with the Austrian army and acting as something of a restraint on the rebellious Hungarian nobility. I will be focussing on the earlier role and the ‘Petit Guerre’ with the Ottomans across the border in Bosnia.

The earliest forces in the border zone were simply hardy individuals of the local population, joined by warlike refugees who created small warrior communities free from the local nobility. As the Ottoman pressure relented somewhat, these communities were forced to choose between submission to state power as peasant-soldiers, or returning to a form of serfdom. They chose the military.

By the middle of the 18th Century the Militargrenze covered the entire border with the Ottomans, from the Adriatic to the Carpathians, 1000 miles long and 20 to 36 miles wide. These were crown lands assigned to military colonists, were all men capable of bearing arms (Grenzer) were part of an ever-ready military force. In the early period they elected their own captains (vojvode), kept a share of booty and most importantly, were allowed religious freedom as mainly Orthodox Christians in a Catholic state. They lived in fortified villages, blockhouses and watchtowers, financed by the Inner Austrian estates, not the Croatian Ban, to emphasise their link to the Hapsburgs and their separate status.

This status was set out in 1630 in the Statuta Valachorum. This made the Zadruga, a large joint-family household the basis of the land grant. The main advantage over a single-family farm was that the loss of an adult male could be absorbed. While they continued to elect their Vojvode, these officers became accountable to Austrian officers based at the Karlstadt fortress covering the Karlstadt and Warasdin Generalcies. A third Croatian district was added, Banal Granitz, during the recovery of territory from the Ottomans at the end of the 17th Century. All three districts gained troops from the migration of some Serbian 30,000 families after the Treaty of Karlowitz ended the war in 1699.

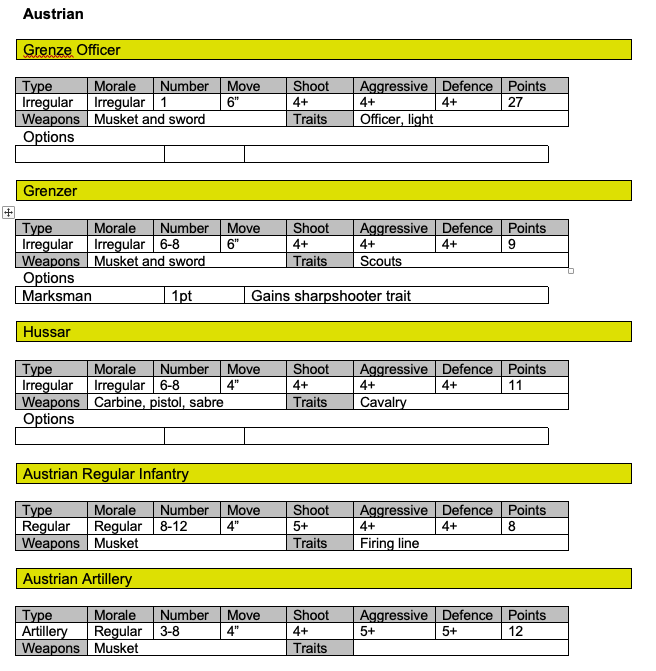

The system suffered from neglect by the end of the century and planned reforms were not implemented. However, Grenzer were an important, if unruly, element of Austrian armies in the War of the Austrian Succession. By 1750 the Militargrenze was reorganised from an irregular frontier militia into a disciplined force of foot and hussar regiments.

The Habsburgs maintained a military zone, the Militargrenze, along Croatia’s southern border for over 350 years, from 1522 to 1881. The original purpose was a defensive screen against Ottoman incursions. Later it became an important Habsburg military institution, fighting with the Austrian army and acting as something of a restraint on the rebellious Hungarian nobility. I will be focussing on the earlier role and the ‘Petit Guerre’ with the Ottomans across the border in Bosnia.

The earliest forces in the border zone were simply hardy individuals of the local population, joined by warlike refugees who created small warrior communities free from the local nobility. As the Ottoman pressure relented somewhat, these communities were forced to choose between submission to state power as peasant-soldiers, or returning to a form of serfdom. They chose the military.

By the middle of the 18th Century the Militargrenze covered the entire border with the Ottomans, from the Adriatic to the Carpathians, 1000 miles long and 20 to 36 miles wide. These were crown lands assigned to military colonists, were all men capable of bearing arms (Grenzer) were part of an ever-ready military force. In the early period they elected their own captains (vojvode), kept a share of booty and most importantly, were allowed religious freedom as mainly Orthodox Christians in a Catholic state. They lived in fortified villages, blockhouses and watchtowers, financed by the Inner Austrian estates, not the Croatian Ban, to emphasise their link to the Hapsburgs and their separate status.

This status was set out in 1630 in the Statuta Valachorum. This made the Zadruga, a large joint-family household the basis of the land grant. The main advantage over a single-family farm was that the loss of an adult male could be absorbed. While they continued to elect their Vojvode, these officers became accountable to Austrian officers based at the Karlstadt fortress covering the Karlstadt and Warasdin Generalcies. A third Croatian district was added, Banal Granitz, during the recovery of territory from the Ottomans at the end of the 17th Century. All three districts gained troops from the migration of some Serbian 30,000 families after the Treaty of Karlowitz ended the war in 1699.

The system suffered from neglect by the end of the century and planned reforms were not implemented. However, Grenzer were an important, if unruly, element of Austrian armies in the War of the Austrian Succession. By 1750 the Militargrenze was reorganised from an irregular frontier militia into a disciplined force of foot and hussar regiments.

|

National identity was at best confused during this period, with Croats, Serbs and Bosnians all fighting over the border. In more recent times this has been a source of conflict, as illustrated by this morbid joke:

“A Croat, a Bosniak and two Serbs arrive on the moon. The Croat points to the lunar mountains and says, “These are like the Dalmatian Hills - this must be Croat land”. The Bosniak argues that the cratered surface resembles the shell-scarred roads of Sarajevo, “so it must be Bosnian”. One of the Serbs pulls out a gun, shoots the other Serb and says, “A Serb has died here – this is Serb land”.” This view is not limited to the Serbs - you could substitute any of the nationalities in this joke! |

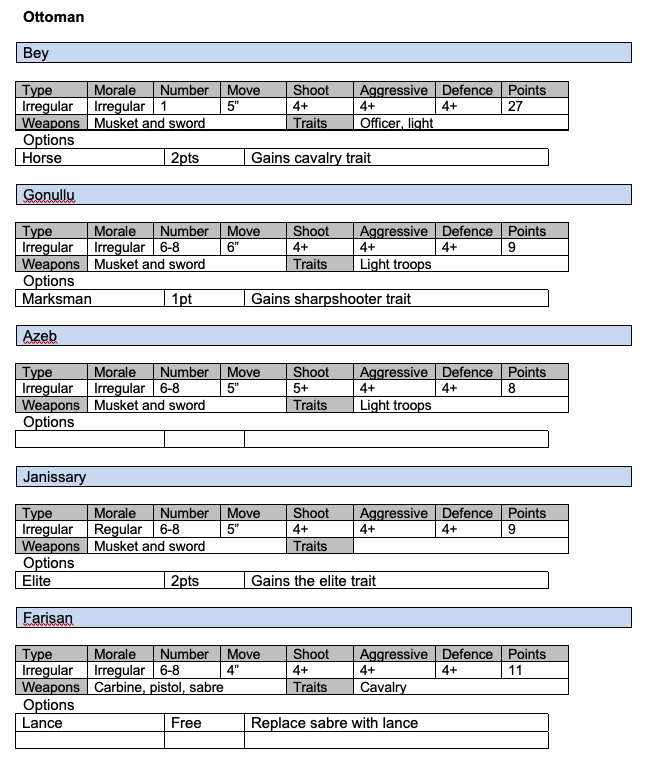

The Ottoman Frontier

Frontier society had a long tradition within the Ottoman state. The Seljuk Turks established military districts on their frontiers as basis for defence and raiding. These developed into Beyliks and the Ottoman Empire began as one such district. Raiding was not only lucrative, but it constituted a religious war for the Faith and the fighters became gazis.

As with the Habsburg side, the border attracted young men to begin a new life unconstrained by the system. Volunteers, called gonullus, took over from the gazis bands as infantry and cavalry. They served under the local fortress commander but did not receive any pay until the 16th Century, when they were organised into units like the Janissaries, Azebs, Farisan (cavalry) and Topcu (gunners). However, booty from raids, livestock and captives was still an important supplement to a soldiers normal, and often erratic pay.

There are a bewildering number of descriptions of troop types in Ottoman records, but they certainly included Christian troops who joined the Ottoman military as Martolos under Muslim officers. These were fortress troops although they joined raids and shared in the proceeds. Over time it appears that many converted to Islam. Other Christians served as Derbends, guarding roads and mountain passes. Sekban units were regarded as inferior to Azebs and were used extensively in sieges. These could be of any faith, but Muslim units were regarded as more reliable.

Outside the major fortresses, troops were based in smaller forts, called palanka. These were wood palisades surrounded by a ditch. The larger ones had two rows of tree trunks with earth in between and could have some stone works as well.

For some idea of numbers, there were 20,939 militia troops in Bosnia at the outbreak of war in 1737, based in fortresses and palankas. The major Banaluka fortress had 1105 men divided into four infantry Azeb units, nine Farisan cavalry units and two Martolos light infantry units with supporting artillery. An additional 437, most infantry, held the outer palankas.

The Ottoman system worked well in 17th Century but started to decline in the 18th and 19th centuries as the financial and bureaucratic problems overwhelmed the Empire’s ability to cope with them.

Frontier society had a long tradition within the Ottoman state. The Seljuk Turks established military districts on their frontiers as basis for defence and raiding. These developed into Beyliks and the Ottoman Empire began as one such district. Raiding was not only lucrative, but it constituted a religious war for the Faith and the fighters became gazis.

As with the Habsburg side, the border attracted young men to begin a new life unconstrained by the system. Volunteers, called gonullus, took over from the gazis bands as infantry and cavalry. They served under the local fortress commander but did not receive any pay until the 16th Century, when they were organised into units like the Janissaries, Azebs, Farisan (cavalry) and Topcu (gunners). However, booty from raids, livestock and captives was still an important supplement to a soldiers normal, and often erratic pay.

There are a bewildering number of descriptions of troop types in Ottoman records, but they certainly included Christian troops who joined the Ottoman military as Martolos under Muslim officers. These were fortress troops although they joined raids and shared in the proceeds. Over time it appears that many converted to Islam. Other Christians served as Derbends, guarding roads and mountain passes. Sekban units were regarded as inferior to Azebs and were used extensively in sieges. These could be of any faith, but Muslim units were regarded as more reliable.

Outside the major fortresses, troops were based in smaller forts, called palanka. These were wood palisades surrounded by a ditch. The larger ones had two rows of tree trunks with earth in between and could have some stone works as well.

For some idea of numbers, there were 20,939 militia troops in Bosnia at the outbreak of war in 1737, based in fortresses and palankas. The major Banaluka fortress had 1105 men divided into four infantry Azeb units, nine Farisan cavalry units and two Martolos light infantry units with supporting artillery. An additional 437, most infantry, held the outer palankas.

The Ottoman system worked well in 17th Century but started to decline in the 18th and 19th centuries as the financial and bureaucratic problems overwhelmed the Empire’s ability to cope with them.

Warfare

Troops on both sides of the border had an interest in keeping the level of violence in check. Raids that were too large attracted attention from central authorities, whereas ‘petit guerre’ was not regarded as war. There were also informal rules about not slaughtering captives and even some evidence of collusion over tax collection and trade.

Troops on both sides of the border had an interest in keeping the level of violence in check. Raids that were too large attracted attention from central authorities, whereas ‘petit guerre’ was not regarded as war. There were also informal rules about not slaughtering captives and even some evidence of collusion over tax collection and trade.

Further Reading

For the Militargrenze the essential reading is Rothenberg’s two books, ‘The Austrian Military Border in Croatia 1522-1747’ and ‘The Military Border in Croatia 1740-1881’.

For the Ottoman side there is Hickok, ‘Ottoman Military Administration in Eighteenth-Century Bosnia’ and a 2001 PhD dissertation by Mark Stein, ‘Seventeenth-Century Ottoman Forts and Garrisons on the Habsburg Frontier.

Sadly, most of these are either difficult to get hold of or expensive. Somewhat easier to access is John Stoye’s, ‘Marsigli’s Europe’, about a Habsburg officer who travelled extensively in the Balkans in the early 18th Century.

For the Militargrenze the essential reading is Rothenberg’s two books, ‘The Austrian Military Border in Croatia 1522-1747’ and ‘The Military Border in Croatia 1740-1881’.

For the Ottoman side there is Hickok, ‘Ottoman Military Administration in Eighteenth-Century Bosnia’ and a 2001 PhD dissertation by Mark Stein, ‘Seventeenth-Century Ottoman Forts and Garrisons on the Habsburg Frontier.

Sadly, most of these are either difficult to get hold of or expensive. Somewhat easier to access is John Stoye’s, ‘Marsigli’s Europe’, about a Habsburg officer who travelled extensively in the Balkans in the early 18th Century.