- Home

- About

-

Travel

-

Features

- Dyrrachion1081

- Normans in the Balkans

- Manolada 1316

- Kosovo 1389

- Castles on the Danube

- Late Medieval Bosnian Army

- Doboj 1415

- Wallachian and Moldovan troops of the Napoleonic wars

- Anchialos 917

- Slovenian Borderlands

- The Zadruga and the Military Border

- Cretan War in the Adriatic

- Salonika 1916

- Uskoks of Senj

- Siege of Klis 1537

- Eugene in the Balkans

- Moldavian Surprise 1711

- Austro-Turkish War 1737-9

- Militargrenze

- Invading Ottoman Turkey

- Siege of Ragusa 1814

- Russo-Turkish War 1806-12

- Serbian Uprising 1815

- Ali Pasha

- Ottoman Army 1826

- Aleksinac 1876

- Shipka Pass

- Slivnitsa 1885

- Romanian Army 1878

- Austrian forts 19thC

- Kumanovo 1912

- Catalca Lines

- Adrianople 1912-13

- Kajmakcalan 1916

- The other 1918 campaign

- Macedonia air war WW1

- War of the Stray Dog

- Royal Yugoslavian armed forces

- Blunder in the Mountains

- Romanian SS

- Gebirgsjager in the Balkans

- Knights Move 1944

- Vis during WW2

- HLI in the Adriatic

- Adriatic Cruel Seas

- Dalmatian Bridgehead

- Cyprus 1974

- Transnistrian War

- Ottoman Navy Napoleonic wars

- Medieval Balkans

- Balkan lockdown quiz >

- Reviews

-

Armies

- Ancient Greeks

- Pyrrhic army of Epirus

- Dacian wars

- Goths

- Late Roman

- Comnenan Byzantine Army

- Normans

- Serbian medieval

- Albanian medieval

- Wallachian medieval

- Bosnian Medieval

- Catalan Company

- Polish 17C

- Austrian Imperialist

- Ottoman

- Austrian 18thC

- Russian Early 18thC

- Ottoman Napoleonic

- Greek Revolution

- 1848 Hungarian Revolution

- Russian Crimean war

- Romanian Army of 1877

- Ottoman 1877

- Russian 1877

- Balkan Wars 1912-13

- Macedonia WW1

- Greece WW2

- Italian Army WW2

- Gebirgsjager WW2

- Hungary WW2

- Turkey WW2

- Soviet Union WW2

- Bulgaria WW2

- Turkish Korean War Brigade

- Balkan Wars 1990s

- Links

- Books

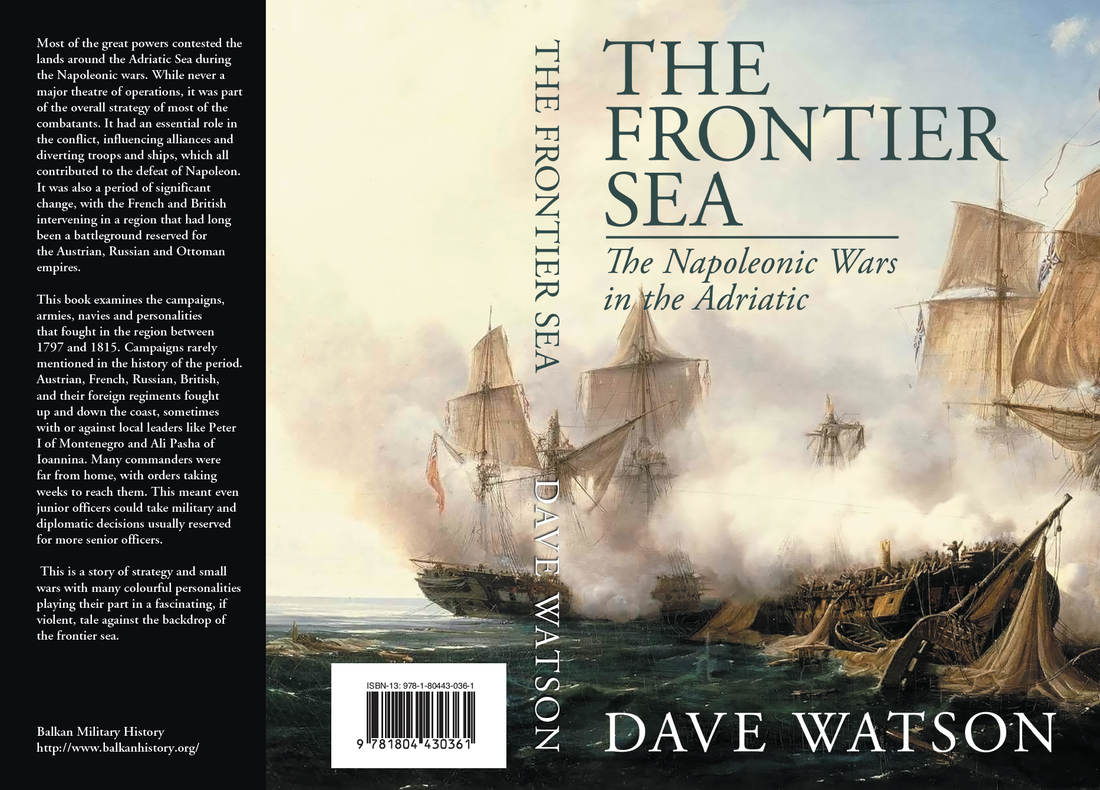

The Frontier Sea: The Napoleonic Wars in the Adriatic

Most of the great powers contested the lands around the Adriatic Sea during the Napoleonic wars. While never a major theatre of operations, it was part of the overall strategy of most of the combatants. It had an essential role in the conflict, influencing alliances and diverting troops and ships, which all contributed to the defeat of Napoleon. It was also a period of significant change, with the French and British intervening in a region that had long been a battleground reserved for the Austrian, Russian and Ottoman empires.

This book examines the campaigns, armies, navies and personalities that fought in the region between 1797 and 1815. Campaigns rarely mentioned in the history of the period. Austrian, French, Russian, British, and their foreign regiments fought up and down the coast. Sometimes with or against local leaders like Peter I of Montenegro and Ali Pasha of Ioannina. Many commanders were far from home, with orders taking weeks to reach them. This meant even junior officers could take military and diplomatic decisions usually reserved for more senior officers.

This is a story of strategy and small wars with many colourful personalities playing their part in a fascinating, if violent, tale against the backdrop of the frontier sea.

Watch an introduction to the book on YouTube.

ISBN: 978-1-80443-036-1 (paperback) - £9.90

ISBN: 978-1-80443-037-8 (ebook) - £8.90

182 pages (Black and White)

6.00 x 9.00 inches

You can order the book through your local bookshop.

Or through Amazon as a paperback or Kindle edition. https://amzn.eu/d/aQ52cpa

Or directly below (UK only).

This book examines the campaigns, armies, navies and personalities that fought in the region between 1797 and 1815. Campaigns rarely mentioned in the history of the period. Austrian, French, Russian, British, and their foreign regiments fought up and down the coast. Sometimes with or against local leaders like Peter I of Montenegro and Ali Pasha of Ioannina. Many commanders were far from home, with orders taking weeks to reach them. This meant even junior officers could take military and diplomatic decisions usually reserved for more senior officers.

This is a story of strategy and small wars with many colourful personalities playing their part in a fascinating, if violent, tale against the backdrop of the frontier sea.

Watch an introduction to the book on YouTube.

ISBN: 978-1-80443-036-1 (paperback) - £9.90

ISBN: 978-1-80443-037-8 (ebook) - £8.90

182 pages (Black and White)

6.00 x 9.00 inches

You can order the book through your local bookshop.

Or through Amazon as a paperback or Kindle edition. https://amzn.eu/d/aQ52cpa

Or directly below (UK only).

The Frontier Sea: The Napoleonic Wars in the Adriatic

£9.90

This book examines the campaigns, armies, navies and personalities that fought in the eastern Adriatic between 1797 and 1815. Austrian, French, Russian, British, and their foreign regiments fought up and down the coast. Sometimes with or against local leaders like Peter I of Montenegro and Ali Pasha of Ioannina.

This is a story of strategy and small wars with many colourful personalities playing their part in a fascinating, if violent, tale against the backdrop of the frontier sea.

Extracts

Prologue

Life in the Royal Navy could be brutal. Lieutenant Donat Henchy O’Brien viewed the gun deck of the frigate HMS Amphion after the Battle of Lissa in 1811, ‘It would be difficult to describe the horrors which now presented themselves. The carnage was dreadful – the dead and dying lying about in every direction; the cries of the latter were most lamentable and piercing.’

A double-shotted cannonball fired from an 18-pdr gun could do terrible damage. As O’Brien explained, ‘Strange to say, every man stationed at one of the guns had been killed, and as it was supposed by the same shots, which passed through both sides of the ship into the sea. At another gun the skull of one poor creature was lodged in the beam above where he stood, the shot having taken an oblique direction: in short, the scene was heart-rending and sickening.’ If the actual fighting was not bad enough, sailors in the Adriatic faced a wind called the bora. A Russian naval officer, Midshipman Vladimir Bronevskiy, said, ‘it was so strong that it can be compared to a terrible hurricane.’ His frigate rolled on its side, masts cracked, and scraps of torn sail flew by.

It was pretty challenging on land as well, particularly if you were a French soldier struggling down the tracks that passed for roads in Dalmatia, with the threat of ambush around every corner. There was no prison camp for those captured by the Montenegrins, who cut off the heads of enemies who fell into their hands. They were no less ruthless with their own and allied wounded. An older, somewhat overweight Russian officer fell from exhaustion during a retreat from a raid. A Montenegrin rushed to him and drew his sword, saying, ‘you’re very brave and must wish that I take your head. Say a prayer and cross yourself.’ Unsurprisingly, the Russian gathered his strength and caught up! If this sounds grim, you certainly wouldn’t want to get on the wrong side of the Ottoman ruler Ali Pasha. Every French soldier captured by him at the Greek port of Preveza was given a razor with which he was forced to skin the severed heads of his compatriots.

Garrison duty should have been a rest, with the attractions of cheap wine and friendly local women. However, Lieutenant John Hildebrand of the 35th Foot described one barracks as having ‘a large admixture of fleas of the largest size and in high condition.’ Soldiers stripped naked to get rid of them from their uniforms, shaking out ‘large lumps of fleas, in balls formed by their tenacious clinging to each other and one would fancy almost devouring each other, a truly wonderful and disgusting sight! So strange as hardly to be believed excepting by those who beheld it.’

However, there were some compensations. The weather was generally pleasant when the bora or the mistral winds did not blow. It could also be profitable for naval officers and crews who acquired prize money from the many ships they captured. The local merchants and ship owners were less enthusiastic about the impact on the local economy! Captain William Hoste wrote home to his father, ‘We have plenty of work cut out for us in the Adriatic, and of all stations it is the pleasantest: such variety and amusement, and prizes to boot, make the hours pass quick, I assure you.’

We will meet these characters and many others in our story. The French, Italian, British, Austrian, Russian, Ottoman and the local soldiers and sailors who plied their trade in the Adriatic during the Napoleonic wars.

Life in the Royal Navy could be brutal. Lieutenant Donat Henchy O’Brien viewed the gun deck of the frigate HMS Amphion after the Battle of Lissa in 1811, ‘It would be difficult to describe the horrors which now presented themselves. The carnage was dreadful – the dead and dying lying about in every direction; the cries of the latter were most lamentable and piercing.’

A double-shotted cannonball fired from an 18-pdr gun could do terrible damage. As O’Brien explained, ‘Strange to say, every man stationed at one of the guns had been killed, and as it was supposed by the same shots, which passed through both sides of the ship into the sea. At another gun the skull of one poor creature was lodged in the beam above where he stood, the shot having taken an oblique direction: in short, the scene was heart-rending and sickening.’ If the actual fighting was not bad enough, sailors in the Adriatic faced a wind called the bora. A Russian naval officer, Midshipman Vladimir Bronevskiy, said, ‘it was so strong that it can be compared to a terrible hurricane.’ His frigate rolled on its side, masts cracked, and scraps of torn sail flew by.

It was pretty challenging on land as well, particularly if you were a French soldier struggling down the tracks that passed for roads in Dalmatia, with the threat of ambush around every corner. There was no prison camp for those captured by the Montenegrins, who cut off the heads of enemies who fell into their hands. They were no less ruthless with their own and allied wounded. An older, somewhat overweight Russian officer fell from exhaustion during a retreat from a raid. A Montenegrin rushed to him and drew his sword, saying, ‘you’re very brave and must wish that I take your head. Say a prayer and cross yourself.’ Unsurprisingly, the Russian gathered his strength and caught up! If this sounds grim, you certainly wouldn’t want to get on the wrong side of the Ottoman ruler Ali Pasha. Every French soldier captured by him at the Greek port of Preveza was given a razor with which he was forced to skin the severed heads of his compatriots.

Garrison duty should have been a rest, with the attractions of cheap wine and friendly local women. However, Lieutenant John Hildebrand of the 35th Foot described one barracks as having ‘a large admixture of fleas of the largest size and in high condition.’ Soldiers stripped naked to get rid of them from their uniforms, shaking out ‘large lumps of fleas, in balls formed by their tenacious clinging to each other and one would fancy almost devouring each other, a truly wonderful and disgusting sight! So strange as hardly to be believed excepting by those who beheld it.’

However, there were some compensations. The weather was generally pleasant when the bora or the mistral winds did not blow. It could also be profitable for naval officers and crews who acquired prize money from the many ships they captured. The local merchants and ship owners were less enthusiastic about the impact on the local economy! Captain William Hoste wrote home to his father, ‘We have plenty of work cut out for us in the Adriatic, and of all stations it is the pleasantest: such variety and amusement, and prizes to boot, make the hours pass quick, I assure you.’

We will meet these characters and many others in our story. The French, Italian, British, Austrian, Russian, Ottoman and the local soldiers and sailors who plied their trade in the Adriatic during the Napoleonic wars.

Introduction

The Adriatic Sea is thought to be named after the Etruscan colony of Adria, founded in 1376 BCE, once the most important town in the Adriatic but now in ruins. The Adriatic is about 460 miles long and generally between 90 and 110 miles wide, although only 37 miles wide at its narrowest point. The area covered by the Adriatic is around 40,000 square miles. The western Italian coast is generally low-lying and navigable, with few major ports. In contrast, the eastern shore has high mountains and deep water, bordered by islands and rocks, which make navigation challenging.

The focus of this story is the region on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea from Istria (in modern Croatia) in the north to Albania and Greece in the south. The coastline is mainly a narrow belt of land dominated by the Dinaric Alps, which helped create a hinterland utterly different from the more urbanised and prosperous coast. Seventy-nine islands run almost parallel to the coast, the largest being Brač, Pag, Hvar, and further south, Corfu. Because of their position on the coastal shipping lanes which joined the western and eastern world, the Adriatic islands have often played an important historical role. The coastal cities were not large during this period. They included Trieste in the north, Rijeka, Zadar, Split, Ragusa (Dubrovnik), Cattaro (Kotor) and Ioannina (in modern Greece) in the south. However, the Adriatic conflict did not operate in isolation. The Ottomans had broader concerns in the Balkans, not least perennial war with the Russians and internal disputes. The British campaign was directed mainly from Sicily, meaning that events in Naples and later Spain often dominated their plans. For the French, Russians and Austrians, the campaigns in central Europe were decisive. The Austrian and Ottoman empires faced each other on the coast and inland in a border area that, by our period, became known as Krajina.

Much has been written about the land borders in the Balkans, the scene of violent conflicts for centuries. However, the Adriatic Sea itself was a key extension of those borderlands. What the sociologist Emilio Cocco called the ‘maritime counterpart to the [Balkan] space poised between East and West.’ A frontier that was contested fiercely over by Venice and Ottoman empires just before our period became even more fluid as the French, British and Russians entered the Adriatic. A porous boundary that is difficult to capture in a line on a map but still a marker of identity for those who lived beside it – a frontier of the sea.

Our story begins with the French Revolutionary Wars that brought the French armies into the Adriatic due to their victories in Italy. Historians differ over when the Revolutionary Wars ended, and the Napoleonic Wars started. Still, for our purposes, Napoleon led the French forces in our area throughout the period. Napoleon Bonaparte captured Venice on 12 May 1797 during the War of the First Coalition. While Austria gained Venice under the Treaty of Campo Formio (12 October 1797), the Ionian Islands off the Greek coast were ceded to France. We will cover the subsequent conflicts that resulted in the territories shifting control amongst the great powers of the day. In addition to France and Austria, the Ottoman Empire held Bosnia and, on paper, Montenegro, Albania and Greece. However, in practice, the Montenegrins acted independently, as did another key character in our story, Ali Pasha, who controlled much of Albania and northwest Greece. Other powers intervened in the region. The Russians captured the Ionian Islands in 1799, although they surrendered them in 1807. They also engaged in one of many wars against the Ottomans that in the 19th century were less about capturing ‘Russian’ lands and more about the Slavic peoples of the Balkans and control of the Straits. The British dominated the Adriatic Sea from bases in the Ionian Islands and the island of Lissa (Vis) in 1812. Our story ends in 1814 when the French abandoned the Ionian Islands.

This theatre of operations is geographically detached from the main battlefields of the Napoleonic Wars, although it was active throughout the conflict and impacted the overall war effort of the participants. In his history of the Napoleonic Wars David Gates described it as the ‘minestrone soup’, meaning all the great powers had an interest and dabbled in it. Communications in the Napoleonic era were slow, with a message taking weeks to reach the commander on the spot. This meant commanders had much more freedom of operation than their colleagues elsewhere. This was true for all the nations involved. Paris to Ragusa (Dubrovnik) is a journey of almost 2,000km along roads that were often little more than dirt tracks. From Moscow, the same destination is nearly 3,000km. Students of Wellington will know he strongly discouraged independent action, in fairness, not least because he had command of Britain’s only significant army. But this level of control was not possible in the Adriatic, 2,200km from London and nearly 900km (including a sea journey) from the theatre commander based in Sicily. We will hear from the memoirs of John Hildebrand (35th Foot) how even a lowly subaltern was given an independent command. Naval commanders were more used to individual initiative. Still, even they could find themselves having to take military and sometimes diplomatic decisions that would usually be reserved for more senior officers.

British naval power was crucial to achieving the strategic objectives in the Adriatic and the wider Mediterranean, but it was not decisive. As Palmerston put it, ‘ships sailing on the sea cannot stop armies on land.’ However, the Royal Navy did achieve this in a limited way in the Adriatic. British subsidies, funded by trade and economic strength, were a critical factor influencing warfare on land. A historical tradition connects British policy in the region to a fear of Napoleon invading India. While Napoleon may have had such a dream, it wasn’t realistic, even when allied to Tsar Paul of Russia. He only visited the northern tip of the Adriatic himself , but he saw himself in historical terms. Writing later in St Helena, he recalled, ‘Greece awaits a liberator. What a splendid wreath of glory is there! He can inscribe his name for eternity with those of Homer, of Plato, of Epaminondas! When at the time of campaign of Italy I touched the shores of the Adriatic, I wrote to the Directoire that I could look out over the Empire of Alexander.’

British policy was focused more on the Ottoman Empire, whose collapse would have allowed France to grab the spoils. French progress down the Dalmatian coast, mainly at Austrian expense, reduced the buffer between the French and Ottoman empires. Austria was Britain’s leading ally during these wars, and British subsidies kept them in the conflict. They were France’s most consistent enemy, joining all bar one of the coalitions formed to fight them. The Ottoman Empire is traditionally viewed as being in decline since the reign of Süleyman the Great. In fact, the empire’s boundaries shifted very little in the century after his death. However, much was going on within those borders. As Caroline Finkel explains, border maps are ‘masking the reality that any frontier, however defined, was a place of infinite complication both for the governments that sought to assert their power there, or acknowledged it as the limit of their reach, and for the people whose lives were shaped by its very existence.’ Borderlands are often far from the seat of power and, as we will see, create challenges for the states trying to control them. Diverse populations can learn to live with each other while also perceiving the other as different and hostile, leading to violence. In the Balkans, these borders were also disputed, becoming the scene for wars between the great powers.

There is much debate amongst historians as to how different warfare in the Napoleonic wars was compared with the 18th century. The armies were indeed larger, sustained by revolutionary France by extracting resources from conquered territories and reorganisation of French society. The revolution created an officer class dominated by talent rather than birth. However, the loss of experienced officers had a bigger impact on the fleet, which was crucial in the Adriatic. As Jeremy Black argues , the tactical changes represented a continuation of tendencies already adopted, such as rapid movement and battlefield artillery; the crucial difference was numbers. Napoleon may have inherited these changes, but he did bring self-confidence, swift decision-making, mobility, and the concentration of forces. Historians also differ over the blame for the wars that caused much suffering in this region as they did in the rest of Europe. Charles Esdaile argues that the responsibility was Napoleon’s ‘and his alone.’ While accepting that Napoleon played a major role in provoking the wars, David Gates argues, ‘he assuredly did not start them all.’ He points in particular to Austria’s conduct, but also the other belligerents played their part. Charles Esdaile does have a point when he argues the impact of revolutionary ideology was somewhat blunted in Italy and the Balkans by the looting and depredations of the French army. Revolts and desertion rates amongst locally raised troops were exceptionally high. However, it had longer-term consequences, influencing the nationalist movements later in the century. The ancien regimes paid the price for failing to address these developments at the Congress of Vienna at the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars. For the Ottomans, acquiring new weaponry was not enough; the failure to reform the civil and military structures underpinned their failures.

As the great Napoleonic historian David Chandler said, ‘I have never underestimated the value of wargaming as an aid to serious study as well as a means of relaxation.’ As he recognised, it is no surprise that the Napoleonic Wars are popular with wargamers. The battles of the coalitions against Napoleon, the Peninsular War, and finally, Waterloo are regularly fought on the tabletop. However, the campaigns in the Adriatic offer something different, both in scale and variety. We will explore these options and offer some scenarios in Appendix 2.

Place names in the Balkans are a perennial challenge for the writer and reader. I have generally used place names as they were described during this period, although with alternatives and modern names in brackets. The Ottomans create a further complexity, and I generally refer to the Ottoman Empire rather than the everyday use of Turkey or today, Türkiye. The Porte is used as a shorthand for the Sublime Porte when referring to actions of the Ottoman administration and diplomatic exchanges. I prefer Istanbul to Constantinople to reflect the Ottoman control of the city and the gradual shift in use. However, it can be argued that this didn’t formally change until the Turkish Post Office officially changed the name in 1930. The Ottomans and other South Slavic languages also confusingly called the Mediterranean, or the Aegean, the White Sea. Dates can also confuse as some countries still used the Julian calendar in this period, and I generally refer to the modern calendar. There are some chronological overlaps in the narrative because it was better to finish a particular campaign. A single narrative wouldn’t accommodate the complex interventions by local and external actors or capture some of the distinct features of warfare in this region. There is a chronology in Appendix 1.

The Adriatic Sea is thought to be named after the Etruscan colony of Adria, founded in 1376 BCE, once the most important town in the Adriatic but now in ruins. The Adriatic is about 460 miles long and generally between 90 and 110 miles wide, although only 37 miles wide at its narrowest point. The area covered by the Adriatic is around 40,000 square miles. The western Italian coast is generally low-lying and navigable, with few major ports. In contrast, the eastern shore has high mountains and deep water, bordered by islands and rocks, which make navigation challenging.

The focus of this story is the region on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea from Istria (in modern Croatia) in the north to Albania and Greece in the south. The coastline is mainly a narrow belt of land dominated by the Dinaric Alps, which helped create a hinterland utterly different from the more urbanised and prosperous coast. Seventy-nine islands run almost parallel to the coast, the largest being Brač, Pag, Hvar, and further south, Corfu. Because of their position on the coastal shipping lanes which joined the western and eastern world, the Adriatic islands have often played an important historical role. The coastal cities were not large during this period. They included Trieste in the north, Rijeka, Zadar, Split, Ragusa (Dubrovnik), Cattaro (Kotor) and Ioannina (in modern Greece) in the south. However, the Adriatic conflict did not operate in isolation. The Ottomans had broader concerns in the Balkans, not least perennial war with the Russians and internal disputes. The British campaign was directed mainly from Sicily, meaning that events in Naples and later Spain often dominated their plans. For the French, Russians and Austrians, the campaigns in central Europe were decisive. The Austrian and Ottoman empires faced each other on the coast and inland in a border area that, by our period, became known as Krajina.

Much has been written about the land borders in the Balkans, the scene of violent conflicts for centuries. However, the Adriatic Sea itself was a key extension of those borderlands. What the sociologist Emilio Cocco called the ‘maritime counterpart to the [Balkan] space poised between East and West.’ A frontier that was contested fiercely over by Venice and Ottoman empires just before our period became even more fluid as the French, British and Russians entered the Adriatic. A porous boundary that is difficult to capture in a line on a map but still a marker of identity for those who lived beside it – a frontier of the sea.

Our story begins with the French Revolutionary Wars that brought the French armies into the Adriatic due to their victories in Italy. Historians differ over when the Revolutionary Wars ended, and the Napoleonic Wars started. Still, for our purposes, Napoleon led the French forces in our area throughout the period. Napoleon Bonaparte captured Venice on 12 May 1797 during the War of the First Coalition. While Austria gained Venice under the Treaty of Campo Formio (12 October 1797), the Ionian Islands off the Greek coast were ceded to France. We will cover the subsequent conflicts that resulted in the territories shifting control amongst the great powers of the day. In addition to France and Austria, the Ottoman Empire held Bosnia and, on paper, Montenegro, Albania and Greece. However, in practice, the Montenegrins acted independently, as did another key character in our story, Ali Pasha, who controlled much of Albania and northwest Greece. Other powers intervened in the region. The Russians captured the Ionian Islands in 1799, although they surrendered them in 1807. They also engaged in one of many wars against the Ottomans that in the 19th century were less about capturing ‘Russian’ lands and more about the Slavic peoples of the Balkans and control of the Straits. The British dominated the Adriatic Sea from bases in the Ionian Islands and the island of Lissa (Vis) in 1812. Our story ends in 1814 when the French abandoned the Ionian Islands.

This theatre of operations is geographically detached from the main battlefields of the Napoleonic Wars, although it was active throughout the conflict and impacted the overall war effort of the participants. In his history of the Napoleonic Wars David Gates described it as the ‘minestrone soup’, meaning all the great powers had an interest and dabbled in it. Communications in the Napoleonic era were slow, with a message taking weeks to reach the commander on the spot. This meant commanders had much more freedom of operation than their colleagues elsewhere. This was true for all the nations involved. Paris to Ragusa (Dubrovnik) is a journey of almost 2,000km along roads that were often little more than dirt tracks. From Moscow, the same destination is nearly 3,000km. Students of Wellington will know he strongly discouraged independent action, in fairness, not least because he had command of Britain’s only significant army. But this level of control was not possible in the Adriatic, 2,200km from London and nearly 900km (including a sea journey) from the theatre commander based in Sicily. We will hear from the memoirs of John Hildebrand (35th Foot) how even a lowly subaltern was given an independent command. Naval commanders were more used to individual initiative. Still, even they could find themselves having to take military and sometimes diplomatic decisions that would usually be reserved for more senior officers.

British naval power was crucial to achieving the strategic objectives in the Adriatic and the wider Mediterranean, but it was not decisive. As Palmerston put it, ‘ships sailing on the sea cannot stop armies on land.’ However, the Royal Navy did achieve this in a limited way in the Adriatic. British subsidies, funded by trade and economic strength, were a critical factor influencing warfare on land. A historical tradition connects British policy in the region to a fear of Napoleon invading India. While Napoleon may have had such a dream, it wasn’t realistic, even when allied to Tsar Paul of Russia. He only visited the northern tip of the Adriatic himself , but he saw himself in historical terms. Writing later in St Helena, he recalled, ‘Greece awaits a liberator. What a splendid wreath of glory is there! He can inscribe his name for eternity with those of Homer, of Plato, of Epaminondas! When at the time of campaign of Italy I touched the shores of the Adriatic, I wrote to the Directoire that I could look out over the Empire of Alexander.’

British policy was focused more on the Ottoman Empire, whose collapse would have allowed France to grab the spoils. French progress down the Dalmatian coast, mainly at Austrian expense, reduced the buffer between the French and Ottoman empires. Austria was Britain’s leading ally during these wars, and British subsidies kept them in the conflict. They were France’s most consistent enemy, joining all bar one of the coalitions formed to fight them. The Ottoman Empire is traditionally viewed as being in decline since the reign of Süleyman the Great. In fact, the empire’s boundaries shifted very little in the century after his death. However, much was going on within those borders. As Caroline Finkel explains, border maps are ‘masking the reality that any frontier, however defined, was a place of infinite complication both for the governments that sought to assert their power there, or acknowledged it as the limit of their reach, and for the people whose lives were shaped by its very existence.’ Borderlands are often far from the seat of power and, as we will see, create challenges for the states trying to control them. Diverse populations can learn to live with each other while also perceiving the other as different and hostile, leading to violence. In the Balkans, these borders were also disputed, becoming the scene for wars between the great powers.

There is much debate amongst historians as to how different warfare in the Napoleonic wars was compared with the 18th century. The armies were indeed larger, sustained by revolutionary France by extracting resources from conquered territories and reorganisation of French society. The revolution created an officer class dominated by talent rather than birth. However, the loss of experienced officers had a bigger impact on the fleet, which was crucial in the Adriatic. As Jeremy Black argues , the tactical changes represented a continuation of tendencies already adopted, such as rapid movement and battlefield artillery; the crucial difference was numbers. Napoleon may have inherited these changes, but he did bring self-confidence, swift decision-making, mobility, and the concentration of forces. Historians also differ over the blame for the wars that caused much suffering in this region as they did in the rest of Europe. Charles Esdaile argues that the responsibility was Napoleon’s ‘and his alone.’ While accepting that Napoleon played a major role in provoking the wars, David Gates argues, ‘he assuredly did not start them all.’ He points in particular to Austria’s conduct, but also the other belligerents played their part. Charles Esdaile does have a point when he argues the impact of revolutionary ideology was somewhat blunted in Italy and the Balkans by the looting and depredations of the French army. Revolts and desertion rates amongst locally raised troops were exceptionally high. However, it had longer-term consequences, influencing the nationalist movements later in the century. The ancien regimes paid the price for failing to address these developments at the Congress of Vienna at the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars. For the Ottomans, acquiring new weaponry was not enough; the failure to reform the civil and military structures underpinned their failures.

As the great Napoleonic historian David Chandler said, ‘I have never underestimated the value of wargaming as an aid to serious study as well as a means of relaxation.’ As he recognised, it is no surprise that the Napoleonic Wars are popular with wargamers. The battles of the coalitions against Napoleon, the Peninsular War, and finally, Waterloo are regularly fought on the tabletop. However, the campaigns in the Adriatic offer something different, both in scale and variety. We will explore these options and offer some scenarios in Appendix 2.

Place names in the Balkans are a perennial challenge for the writer and reader. I have generally used place names as they were described during this period, although with alternatives and modern names in brackets. The Ottomans create a further complexity, and I generally refer to the Ottoman Empire rather than the everyday use of Turkey or today, Türkiye. The Porte is used as a shorthand for the Sublime Porte when referring to actions of the Ottoman administration and diplomatic exchanges. I prefer Istanbul to Constantinople to reflect the Ottoman control of the city and the gradual shift in use. However, it can be argued that this didn’t formally change until the Turkish Post Office officially changed the name in 1930. The Ottomans and other South Slavic languages also confusingly called the Mediterranean, or the Aegean, the White Sea. Dates can also confuse as some countries still used the Julian calendar in this period, and I generally refer to the modern calendar. There are some chronological overlaps in the narrative because it was better to finish a particular campaign. A single narrative wouldn’t accommodate the complex interventions by local and external actors or capture some of the distinct features of warfare in this region. There is a chronology in Appendix 1.

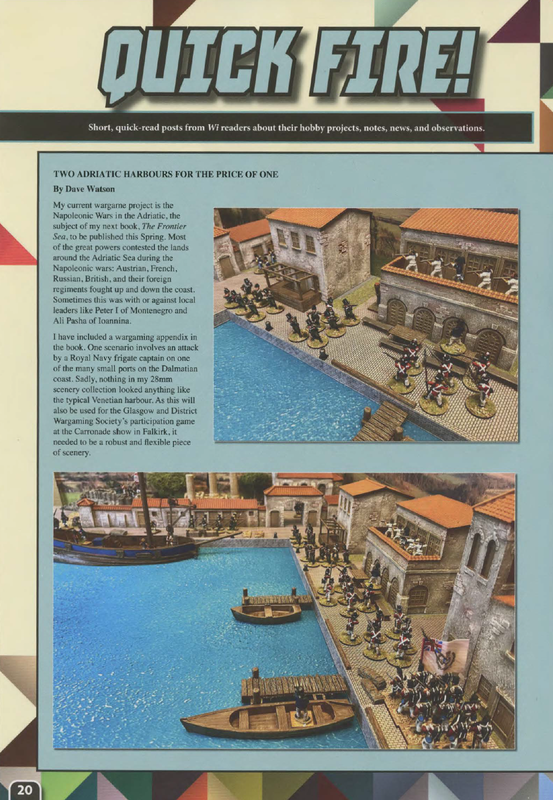

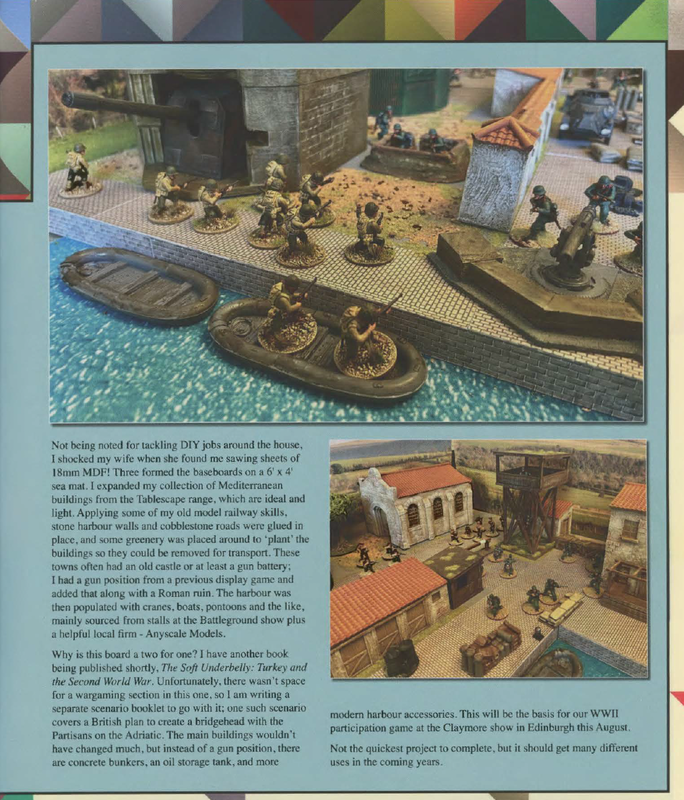

Wargaming the Napoleonic Wars in the Adriatic

|

The book includes an annex on wargaming the Napoleonic Wars in the Adriatic. It includes advice on figure ranges and rules as well as two scenarios to get you started.

Here is a further scenario based on the Siege of Ragusa 1814. And another scenario, the Supply convoy, covering the common British practice of attacking French road convoys on the Dalmatian coast road. Wargame figures For most of the standard troop and ship types, existing Napoleonic ranges in all scales will cover the main combatants in the Adriatic. However, there are a few challenges. Russian wargame figures typically have the post-1809 or 1812 shakos. Brigade Games in the USA have the former 28mm Vitrix range, but this can be an expensive option for European gamers. Several Ottoman ranges include Albanians and other troop types in the region, and irregular troops for the Greek War of Independence work as well. Steve Barber has a good 28mm range, which can be bulked out by Old Glory figures. Old Man’s Creations do some lovely personality figures in resin, including Ali Pasha. Montenegrin troops are similar to the Greeks and Albanians but may need a little conversion work. The are more wargaming resources on the Napoleonic Adriatic page on the editor's blog here. |

|

About the author

Dave Watson was born in Liverpool and has been based in Scotland for

the last thirty-two years. He lives with his wife Liz and Rasputin (the

wargaming cat) in Ayrshire, on the west coast of Scotland.

He is the editor of the website Balkan Military History (www.balkanhistory.

org), which has covered the military history of the Balkans for over twenty-five

years. He has written for many magazines, journals, and online

publications. A list of his publications can be found on this website and his

blog, balkandave.blogspot.com.

He is the author of Chasing the Soft Underbelly: Turkey and the Second

World War (Helion, 2023) and Ripped Apart: The Cyprus Crisis 1963-64 (Helion (2023). In addition, he is a contributing author to the

books A New Scotland (Pluto, 2022), What Would Keir Hardie Say? (Luath,

2015), Keir Hardie and the 21st Century Socialist Revival (Luath, 2019), and

several other current affairs books and publications.

Dave is a graduate in Scots Law from the University of Strathclyde and a

Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. He retired in 2018 from his post as Head

of Policy and Public Affairs at UNISON Scotland and now works part-time as

a policy consultant, and Director of the think tank the Jimmy Reid Foundation.

His passions include wargaming, travel and golf. He is the secretary of

Glasgow and District Wargaming Society—one of the UK’s longest-running

wargame clubs.

You can also follow Dave on Twitter @Balkan_Dave.

Dave Watson was born in Liverpool and has been based in Scotland for

the last thirty-two years. He lives with his wife Liz and Rasputin (the

wargaming cat) in Ayrshire, on the west coast of Scotland.

He is the editor of the website Balkan Military History (www.balkanhistory.

org), which has covered the military history of the Balkans for over twenty-five

years. He has written for many magazines, journals, and online

publications. A list of his publications can be found on this website and his

blog, balkandave.blogspot.com.

He is the author of Chasing the Soft Underbelly: Turkey and the Second

World War (Helion, 2023) and Ripped Apart: The Cyprus Crisis 1963-64 (Helion (2023). In addition, he is a contributing author to the

books A New Scotland (Pluto, 2022), What Would Keir Hardie Say? (Luath,

2015), Keir Hardie and the 21st Century Socialist Revival (Luath, 2019), and

several other current affairs books and publications.

Dave is a graduate in Scots Law from the University of Strathclyde and a

Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. He retired in 2018 from his post as Head

of Policy and Public Affairs at UNISON Scotland and now works part-time as

a policy consultant, and Director of the think tank the Jimmy Reid Foundation.

His passions include wargaming, travel and golf. He is the secretary of

Glasgow and District Wargaming Society—one of the UK’s longest-running

wargame clubs.

You can also follow Dave on Twitter @Balkan_Dave.